Magic & Good Madness: A Neil Gaiman Reread on Tor.com kicks off today and begins in earnest tomorrow with a reread of American Gods, Neil Gaiman’s breathtaking tale of gods old and new as they struggle for relevancy in our world.

Locked behind bars for three years, Shadow has done his time and is quietly waiting for the magic day when he can return to Eagle Point, Indiana. A man no longer scared of what tomorrow might bring, all he wants is to be with Laura, the wife he deeply loves, and to start a new life….

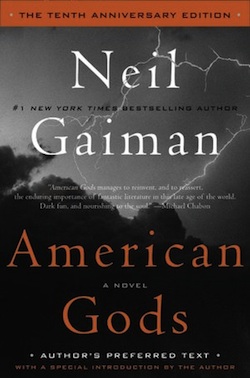

Revisit now the beginning of American Gods, along with the new introduction that Gaiman crafted for its extended, 10th anniversary edition.

An introduction to the Tenth Anniversary Edition of American Gods

I don’t know what it’s like to read this book. I only know what it was like to live the writing of it. I moved to America in 1992. Something started, in the back of my head. There were unrelated ideas that I knew were important and yet seemed unconnected: two men meeting on a plane; the car on the ice; the significance of coin tricks; and more than anything, America: this strange, huge place where I now found myself living that I knew I didn’t understand. But I wanted to understand it. More than that, I wanted to describe it.

And then, during a stopover in Iceland I stared at a tourist diorama of the travels of Leif Erickson, and it all came together. I wrote a letter to my agent and my editor that explained what the book would be. I wrote “American Gods” at the top of the letter, certain I could come up with a better title.

A couple of weeks later, my editor sent me a mock-up of the book cover. It showed a road, and a lightning strike, and, at the top, it said, “American Gods.” It seemed to be the cover of the book I had planned to write.

I found it both off-putting and exhilarating to have the cover before the book. I put it up on the wall and looked at it, intimidated, all thoughts of ever finding another title gone forever. This was the book cover. This was the book.

Now I just had to write it.

I wrote the first chapter on a train journey from Chicago to San Diego. And I kept traveling, and I kept writing. I drove from Minneapolis to Florida by back roads, following routes I thought Shadow would take in the book. I wrote, and sometimes, when I was stuck, I hit the road. I ate pasties in the Upper Peninsula and hush puppies in Cairo. I did my best not to write about any place I had not been.

I wrote my book in many places—houses in Florida, and in a cabin on a Wisconsin lake, and in a hotel room in Las Vegas.

I would follow Shadow on his journey, and when I did not know what happened to Shadow I would write a Coming to America story, and by the time I got to the end of that I would know what Shadow was doing, and so would return to him. I wanted to write two thousand words a day, and if I wrote a thousand words a day I was happy.

I remember when it was all done in first draft telling Gene Wolfe, who is the wisest writer I know and has written more excellent novels than any man I’ve met, that I thought I had now learned how to write a novel. Gene looked at me, and smiled kindly. “You never learn how to write a novel,” he told me. “You only learn to write the novel you’re on.”

He was right. I’d learned to write the novel I was writing, and nothing more. Still, it was a fine, strange novel to have learned how to write. I was always aware of how very far short it fell of the beautiful, golden, gleaming, perfect book I had in my head, but even so, it made me happy.

I grew a beard and I did not cut my hair while I was writing this book, and many people thought I was a trifle odd (although not the Swedes, who approved and told me that a king of theirs had done something very similar, only not with a novel). I shaved the beard off at the end of the first draft, and disposed of the unfeasibly long hair shortly after that.

The second draft was mostly a process of excavation and clarification. Moments that needed to grow grew and moments that needed to be shorter were trimmed.

I wanted it to be a number of things. I wanted to write a book that was big and odd and meandering, and I did and it was. I wanted to write a book that included all the parts of America that obsessed and delighted me, which tended to be the bits that never showed up in the films and television shows.

I finished it, eventually, and I handed it in, taking a certain amount of comfort in the old saying that a novel can best be defined as a long piece of prose with something wrong with it, and I was fairly sure that I’d written one of those.

My editor was concerned that the book I had given to her was slightly too big and too meandering (she didn’t mind it being too odd), and she wanted me to trim it, and I did. I suspect her instincts may have been right, for the book was certainly successful—it sold many copies, and it was fortunate enough to receive a number of awards, including the Nebula and the Hugo (for, primarily, SF), the Bram Stoker (for horror), and the Locus (for fantasy), demonstrating that it may have been a fairly odd novel and that even if it was popular nobody was quite certain which box it belonged in.

But that would be in the future: first the book needed to be published. The publishing process fascinated me and I chronicled it on the web, on a blog I started for that reason (but which has continued to this day). When it was published I went on a book-signing tour, across the U.S., then to the U.K., then to Canada, and finally home. The first book signing I did was in June 2001, at the Borders Books in the World Trade Center. A couple of days after I returned home, on September 11, 2001, neither that bookstore nor the World Trade Center existed.

The reception the book was given surprised me.

I was used to telling stories that people liked, or that they didn’t read. I’d never written anything divisive before. But with this book, people either loved it, or they hated it. The ones who hated it, even if they liked my other books, really hated it. Some people complained that the book was not American enough; others that it was too American; that Shadow was unsympathetic; that I had failed to understand that the true religion of America was sports; and so on. All, undoubtedly, valid criticisms. But in the end, mostly, it found its people. I think it’s fair to say that more people loved it, and continue to love it.

One day, I hope, I will go back to that story. Shadow is ten years older now, after all. So is America. And the Gods are waiting.

Neil Gaiman

September 2010

One question that has always intrigued me is what happens to demonic beings when immigrants move from their homelands. Irish-Americans remember the fairies, Norwegian-Americans the nisser, Greek-Americans the vrykólakas, but only in relation to events remembered in the Old Country. When I once asked why such demons are not seen in America, my informants giggled confusedly and said “They’re scared to pass the ocean, it’s too far,” pointing out that Christ and the apostles never came to America.

—Richard Dorson, “A Theory for American Folklore,”

American Folklore and the Historian

(University of Chicago Press, 1971)

PART ONE

shadows

Chapter One

The boundaries of our country, sir? Why sir, onto the north we are bounded by the Aurora Borealis, on the east we are bounded by the rising sun, on the south we are bounded by the procession of the Equinoxes, and on the west by the Day of Judgement.

—“The American” Joe Miller’s Jest Book

Shadow had done three years in prison. He was big enough, and looked don’t-fuck-with-me enough that his biggest problem was killing time. So he kept himself in shape, and taught himself coin tricks, and thought a lot about how much he loved his wife.

The best thing—in Shadow’s opinion, perhaps the only good thing—about being in prison was a feeling of relief. The feeling that he’d plunged as low as he could plunge and he’d hit bottom. He didn’t worry that the man was going to get him, because the man had got him. He did not awake in prison with a feeling of dread; he was no longer scared of what tomorrow might bring, because yesterday had brought it.

It did not matter, Shadow decided, if you had done what you had been convicted of or not. In his experience everyone he met in prison was aggrieved about something: there was always something the authorities had got wrong, something they said you did when you didn’t—or you didn’t do quite like they said you did. What was important was that they had got you.

He had noticed it in the first few days, when everything, from the slang to the bad food, was new. Despite the misery and the utter skincrawling horror of incarceration, he was breathing relief.

Shadow tried not to talk too much. Somewhere around the middle of year two he mentioned his theory to Low Key Lyesmith, his cellmate.

Low Key, who was a grifter from Minnesota, smiled his scarred smile.

“Yeah,” he said. “That’s true. It’s even better when you’ve been sentenced to death. That’s when you remember the jokes about the guys who kicked their boots off as the noose flipped around their necks, because their friends always told them they’d die with their boots on.”

“Is that a joke?” asked Shadow.

“Damn right. Gallows humor. Best kind there is—bang, the worst has happened. You get a few days for it to sink in, then you’re riding the cart on your way to do the dance on nothing.”

“When did they last hang a man in this state?” asked Shadow.

“How the hell should I know?” Lyesmith kept his orange-blond hair pretty much shaved. You could see the lines of his skull. “Tell you what, though. This country started going to hell when they stopped hanging folks. No gallows dirt. No gallows deals.”

Shadow shrugged. He could see nothing romantic in a death sentence.

If you didn’t have a death sentence, he decided, then prison was, at best, only a temporary reprieve from life, for two reasons. First, life creeps back into prison. There are always places to go further down, even when you’ve been taken off the board; life goes on, even if it’s life under a microscope or life in a cage. And second, if you just hang in there, some day they’re going to have to let you out.

In the beginning it was too far away for Shadow to focus on. Then it became a distant beam of hope, and he learned how to tell himself “this too shall pass” when the prison shit went down, as prison shit always did. One day the magic door would open and he’d walk through it. So he marked off the days on his Songbirds of North America calendar, which was the only calendar they sold in the prison commissary, and the sun went down and he didn’t see it and the sun came up and he didn’t see it. He practiced coin tricks from a book he found in the wasteland of the prison library; and he worked out; and he made lists in his head of what he’d do when he got out of prison.

Shadow’s lists got shorter and shorter. After two years he had it down to three things.

First, he was going to take a bath. A real, long, serious soak, in a tub with bubbles in it. Maybe read the paper, maybe not. Some days he thought one way, some days the other.

Second he was going to towel himself off, put on a robe. Maybe slippers. He liked the idea of slippers. If he smoked he would be smoking a pipe about now, but he didn’t smoke. He would pick up his wife in his arms (“Puppy,” she would squeal in mock horror and real delight, “what are you doing?”). He would carry her into the bedroom, and close the door. They’d call out for pizzas if they got hungry.

Third, after he and Laura had come out of the bedroom, maybe a couple of days later, he was going to keep his head down and stay out of trouble for the rest of his life.

“And then you’ll be happy?” asked Low Key Lyesmith. That day they were working in the prison shop, assembling bird feeders, which was barely more interesting than stamping out license plates.

“Call no man happy,” said Shadow, “until he is dead.”

“Herodotus,” said Low Key. “Hey. You’re learning.”

“Who the fuck’s Herodotus?” asked the Iceman, slotting together the sides of a bird feeder, and passing it to Shadow, who bolted and screwed it tight.

“Dead Greek,” said Shadow.

“My last girlfriend was Greek,” said the Iceman. “The shit her family ate. You would not believe. Like rice wrapped in leaves. Shit like that.”

The Iceman was the same size and shape as a Coke machine, with blue eyes and hair so blond it was almost white. He had beaten the crap out of some guy who had made the mistake of copping a feel off his girlfriend in the bar where she danced and the Iceman bounced. The guy’s friends had called the police, who arrested the Iceman and ran a check on him, which revealed that the Iceman had walked from a work-release program eighteen months earlier.

“So what was I supposed to do?” asked the Iceman, aggrieved, when he had told Shadow the whole sad tale. “I’d told him she was my girlfriend. Was I supposed to let him disrespect me like that? Was I? I mean, he had his hands all over her.”

Shadow had said something meaningless, like “You tell ’em,” and left it at that. One thing he had learned early, you do your own time in prison. You don’t do anyone else’s time for them.

Keep your head down. Do your own time.

Lyesmith had loaned Shadow a battered paperback copy of Herodotus’s Histories several months earlier. “It’s not boring. It’s cool,” he said, when Shadow protested that he didn’t read books. “Read it first, then tell me it’s cool.”

Shadow had made a face, but he had started to read, and had found himself hooked against his will.

“Greeks,” said the Iceman, with disgust. “And it ain’t true what they say about them, neither. I tried giving it to my girlfriend in the ass, she almost clawed my eyes out.”

Lyesmith was transferred one day, without warning. He left Shadow his copy of Herodotus with several actual coins hidden in the pages: two quarters, a penny, and a nickel. Coins were contraband: you can sharpen the edges against a stone, slice open someone’s face in a fight. Shadow didn’t want a weapon; Shadow just wanted something to do with his hands.

Shadow was not superstitious. He did not believe in anything he could not see. Still, he could feel disaster hovering above the prison in those final weeks, just as he had felt it in the days before the robbery. There was a hollowness in the pit of his stomach, which he told himself was simply a fear of going back to the world on the outside. But he could not be sure. He was more paranoid than usual, and in prison usual is very, and is a survival skill. Shadow became more quiet, more shadowy, than ever. He found himself watching the body language of the guards, of the other inmates, searching for a clue to the bad thing that was going to happen, as he was certain that it would.

A month before he was due to be released. Shadow sat in a chilly office, facing a short man with a port-wine birthmark on his forehead. They sat across a desk from each other; the man had Shadow’s file open in front of him, and was holding a ballpoint pen. The end of the pen was badly chewed.

“You cold, Shadow?” “Yes,” said Shadow. “A little.” The man shrugged. “That’s the system,” he said. “Furnaces don’t go on until December the first. Then they go off March the first. I don’t make the rules.” Social niceties done with, he ran his forefinger down the sheet of paper stapled to the inside-left of the folder. “You’re thirty-two years old?”

“Yes, sir.”

“You look younger.”

“Clean living.”

“Says here you’ve been a model inmate.”

“I learned my lesson, sir.”

“Did you? Did you really?” He looked at Shadow intently, the birthmark on his forehead lowering. Shadow thought about telling the man some of his theories about prison, but he said nothing. He nodded, instead, and concentrated on appearing properly remorseful.

“Says here you’ve got a wife, Shadow.”

“Her name’s Laura.”

“How’s everything there?”

“Pretty good. She got kind of mad at me when I was arrested. But she’s come down to see me as much as she could—it’s a long way to travel. We write and I call her when I can.”

“What does your wife do?”

“She’s a travel agent. Sends people all over the world.”

“How’d you meet her?” Shadow could not decide why the man was asking. He considered telling him it was none of his business, then said, “She was my best buddy’s wife’s best friend. They set us up on a blind date. We hit it off.”

“And you’ve got a job waiting for you?”

“Yessir. My buddy, Robbie, the one I just told you about, he owns the Muscle Farm, the place I used to train. He says my old job is waiting for me.”

An eyebrow raised. “Really?”

“Says he figures I’ll be a big draw. Bring back some old-timers, and pull in the tough crowd who want to be tougher.”

The man seemed satisfied. He chewed the end of his ballpoint pen, then turned over the sheet of paper.

“How do you feel about your offense?” Shadow shrugged.

“I was stupid,” he said, and meant it. The man with the birthmark sighed. He ticked off a number of items on a checklist. Then he riffled through the papers in Shadow’s file. “How’re you getting home from here?” he asked. “Greyhound?”

“Flying home. It’s good to have a wife who’s a travel agent.”

The man frowned, and the birthmark creased. “She sent you a ticket?”

“Didn’t need to. Just sent me a confirmation number. Electronic ticket. All I have to do is turn up at the airport in a month and show ’em my ID, and I’m outta here.”

The man nodded, scribbled one final note, then he closed the file and put down the ballpoint pen. Two pale hands rested on the gray desk like pink animals. He brought his hands close together, made a steeple of his forefingers, and stared at Shadow with watery hazel eyes.

“You’re lucky,” he said. “You have someone to go back to, you got a job waiting. You can put all this behind you. You got a second chance. Make the most of it.”

The man did not offer to shake Shadow’s hand as he rose to leave, nor did Shadow expect him to.

The last week was the worst. In some ways it was worse than the whole three years put together. Shadow wondered if it was the weather: oppressive, still and cold. It felt as if a storm was on the way, but the storm never came. He had the jitters and the heebie-jeebies, a feeling deep in his stomach that something was entirely wrong. In the exercise yard the wind gusted. Shadow imagined that he could smell snow on the air.

He called his wife collect. Shadow knew that the phone companies whacked a three-dollar surcharge on every call made from a prison phone. That’s why operators are always real polite to people calling from prisons, Shadow had decided: they knew that he paid their wages.

“Something feels weird,” he told Laura. That wasn’t the first thing he said to her. The first thing was “I love you,” because it’s a good thing to say if you can mean it, and Shadow did.

“Hello,” said Laura. “I love you too. What feels weird?”

“I don’t know,” he said. “Maybe the weather. It feels like if we could only get a storm, everything would be okay.”

“It’s nice here,” she said. “The last of the leaves haven’t quite fallen. If we don’t get a storm, you’ll be able to see them when you get home.”

“Five days,” said Shadow.

“A hundred and twenty hours, and then you come home,” she said.

“Everything okay there? Nothing wrong?”

“Everything’s fine. I’m seeing Robbie tonight. We’re planning your surprise welcome-home party.”

“Surprise party?”

“Of course. You don’t know anything about it, do you?”

“Not a thing.”

“That’s my husband,” she said. Shadow realized that he was smiling. He had been inside for three years, but she could still make him smile.

“Love you, babes,” said Shadow.

“Love you, puppy,” said Laura.

Shadow put down the phone.

When they got married Laura told Shadow that she wanted a puppy, but their landlord had pointed out they weren’t allowed pets under the terms of their lease. “Hey,” Shadow had said, “I’ll be your puppy. What do you want me to do? Chew your slippers? Piss on the kitchen floor? Lick your nose? Sniff your crotch? I bet there’s nothing a puppy can do I can’t do!” And he picked her up as if she weighed nothing at all, and began to lick her nose while she giggled and shrieked, and then he carried her to the bed.

In the food hall Sam Fetisher sidled over to Shadow and smiled, showing his old teeth. He sat down beside Shadow and began to eat his macaroni and cheese.

“We got to talk,” said Sam Fetisher.

Sam Fetisher was one of the blackest men that Shadow had ever seen. He might have been sixty. He might have been eighty. Then again, Shadow had met thirty-year-old crack heads who looked older than Sam Fetisher.

“Mm?” said Shadow.

“Storm’s on the way,” said Sam.

“Feels like it,” said Shadow. “Maybe it’ll snow soon.”

“Not that kind of storm. Bigger storms than that coming. I tell you, boy, you’re better off in here than out on the street when the big storm comes.”

“Done my time,” said Shadow. “Friday, I’m gone.”

Sam Fetisher stared at Shadow. “Where you from?” he asked.

“Eagle Point. Indiana.”

“You’re a lying fuck,” said Sam Fetisher. “I mean originally. Where are your folks from?”

“Chicago,” said Shadow. His mother had lived in Chicago as a girl, and she had died there, half a lifetime ago.

“Like I said. Big storm coming. Keep your head down, Shadow-boy. It’s like . . . what do they call those things continents ride around on? Some kind of plates?”

“Tectonic plates?” Shadow hazarded.

“That’s it. Tectonic plates. It’s like when they go riding, when North America goes skidding into South America, you don’t want to be in the middle. You dig me?”

“Not even a little.”

One brown eye closed in a slow wink. “Hell, don’t say I didn’t warn you,” said Sam Fetisher, and he spooned a trembling lump of orange Jell-O into his mouth.

Shadow spent the night half-awake, drifting in and out of sleep, listening to his new cellmate grunt and snore in the bunk below him. Several cells away a man whined and howled and sobbed like an animal, and from time to time someone would scream at him to shut the fuck up. Shadow tried not to hear. He let the empty minutes wash over him, lonely and slow.

Two days to go. Forty-eight hours, starting with oatmeal and prison coffee and a guard named Wilson who tapped Shadow harder than he had to on the shoulder and said, “Shadow? This way.”

Shadow checked his conscience. It was quiet, which did not, he had observed, in a prison, mean that he was not in deep shit. The two men walked more or less side by side, feet echoing on metal and concrete.

Shadow tasted fear in the back of his throat, bitter as old coffee. The bad thing was happening . . .

There was a voice in the back of his head whispering that they were going to slap another year onto his sentence, drop him into solitary, cut off his hands, cut off his head. He told himself he was being stupid, but his heart was pounding fit to burst out of his chest.

“I don’t get you, Shadow,” said Wilson, as they walked.

“What’s not to get, sir?”

“You. You’re too fucking quiet. Too polite. You wait like the old guys, but you’re what? Twenty-five? Twenty-eight?”

“Thirty-two, sir.”

“And what are you? A spic? A gypsy?”

“Not that I know of, sir. Maybe.”

“Maybe you got nigger blood in you. You got nigger blood in you, Shadow? ”

“Could be, sir.” Shadow stood tall and looked straight ahead, and concentrated on not allowing himself to be riled by this man.

“Yeah? Well, all I know is, you fucking spook me.” Wilson had sandy blond hair and a sandy blond face and a sandy blond smile. “You leaving us soon?”

“Hope so, sir.”

“You’ll be back. I can see it in your eyes. You’re a fuckup, Shadow. Now, if I had my way, none of you assholes would ever get out. We’d drop you in the hole and forget you.”

Oubliettes, thought Shadow, and he said nothing. It was a survival thing: he didn’t answer back, didn’t say anything about job security for prison guards, debate the nature of repentance, rehabilitation, or rates of recidivism. He didn’t say anything funny or clever, and, to be on the safe side, when he was talking to a prison official, whenever possible, he didn’t say anything at all. Speak when you’re spoken to. Do your own time. Get out. Get home. Have a long hot bath. Tell Laura you love her. Rebuild a life.

They walked through a couple of checkpoints. Wilson showed his ID each time. Up a set of stairs, and they were standing outside the prison warden’s office. Shadow had never been there before, but he knew what it was. It had the prison warden’s name—G. Patterson—on the door in black letters, and beside the door, a miniature traffic light.

The top light burned red.

Wilson pressed a button below the traffic light. They stood there in silence for a couple of minutes. Shadow tried to tell himself that everything was all right, that on Friday morning he’d be on the plane up to Eagle Point, but he did not believe it himself.

The red light went out and the green light went on, and Wilson opened the door. They went inside.

Shadow had seen the warden a handful of times in the last three years. Once he had been showing a politician around; Shadow had not recognized the man. Once, during a lock-down, the warden had spoken to them in groups of a hundred, telling them that the prison was overcrowded, and that, since it would remain overcrowded, they had better get used to it. This was Shadow’s first time up close to the man.

Up close, Patterson looked worse. His face was oblong, with gray hair cut into a military bristle cut. He smelled of Old Spice. Behind him was a shelf of books, each with the word prison in the title; his desk was perfectly clean, empty but for a telephone and a tear-off-the-pages Far Side calendar. He had a hearing aid in his right ear.

“Please, sit down.” Shadow sat down at the desk, noting the civility.

Wilson stood behind him.

The warden opened a desk drawer and took out a file, placed it on his desk.

“Says here you were sentenced to six years for aggravated assault and battery. You’ve served three years. You were due to be released on Friday.”

Were? Shadow felt his stomach lurch inside him. He wondered how much longer he was going to have to serve—another year? Two years? All three? All he said was “Yes, sir.”

The warden licked his lips. “What did you say?”

“I said, ‘Yes, sir.’ ”

“Shadow, we’re going to be releasing you later this afternoon. You’ll

be getting out a couple of days early.” The warden said this with no joy, as if he were intoning a death sentence. Shadow nodded, and he waited for the other shoe to drop. The warden looked down at the paper on his desk. “This came from the Johnson Memorial Hospital in Eagle Point . . . Your wife. She died in the early hours of this morning. It was an automobile accident. I’m sorry.”

Shadow nodded once more.

Wilson walked him back to his cell, not saying anything. He unlocked the cell door and let Shadow in. Then he said, “It’s like one of them goodnews, bad-news jokes, isn’t it? Good news, we’re letting you out early, bad news, your wife is dead.” He laughed, as if it were genuinely funny.

Shadow said nothing at all.

•••

Numbly, he packed up his possessions, gave several away. He left behind Low Key’s Herodotus and the book of coin tricks, and, with a momentary pang, he abandoned the blank metal disks he had smuggled out of the workshop which had, until he had found Low Key’s change in the book, served him for coins. There would be coins, real coins, on the outside. He shaved. He dressed in civilian clothes. He walked through door after door, knowing that he would never walk back through them again, feeling empty inside.

The rain had started to gust from the gray sky, a freezing rain. Pellets of ice stung Shadow’s face, while the rain soaked the thin overcoat as they walked away from the prison building, toward the yellow ex–school bus that would take them to the nearest city.

By the time they got to the bus they were soaked. Eight of them were leaving, Shadow thought. Fifteen hundred still inside. He sat on the bus and shivered until the heaters started working, wondering what he was doing, where he was going now.

Ghost images filled his head, unbidden. In his imagination he was leaving another prison, long ago.

He had been imprisoned in a lightless garret room for far too long: his beard was wild and his hair was a tangle. The guards had walked him down a gray stone stairway and out into a plaza filled with brightly colored things, with people and with objects. It was a market day and he was dazzled by the noise and the color, squinting at the sunlight that filled the square, smelling the salt-wet air and all the good things of the market, and on his left the sun glittered from the water. . . .

The bus shuddered to a halt at a red light.

The wind howled about the bus, and the wipers slooshed heavily back and forth across the windshield, smearing the city into a red and yellow neon wetness. It was early afternoon, but it looked like night through the glass.

“Shit,” said the man in the seat behind Shadow, rubbing the condensation from the window with his hand, staring at a wet figure hurrying down the sidewalk. “There’s pussy out there.”

Shadow swallowed. It occurred to him that he had not cried yet—had in fact felt nothing at all. No tears. No sorrow. Nothing.

He found himself thinking about a guy named Johnnie Larch he’d shared a cell with when he’d first been put inside, who told Shadow how he’d once got out after five years behind bars, with $100 and a ticket to Seattle, where his sister lived.

Johnnie Larch had got to the airport, and he handed his ticket to the woman on the counter, and she asked to see his driver’s license.

He showed it to her. It had expired a couple of years earlier. She told him it was not valid as ID. He told her it might not be valid as a driver’s license, but it sure as hell was fine identification, and it had a photo of him on it, and his height and his weight, and damn it, who else did she think he was, if he wasn’t him?

She said she’d thank him to keep his voice down.

He told her to give him a fucking boarding pass, or she was going to regret it, and that he wasn’t going to be disrespected. You don’t let people disrespect you in prison.

Then she pressed a button, and a few moments later the airport security showed up, and they tried to persuade Johnnie Larch to leave the airport quietly, and he did not wish to leave, and there was something of an altercation.

The upshot of it all was that Johnnie Larch never actually made it to Seattle, and he spent the next couple of days in town in bars, and when his $100 was gone he held up a gas station with a toy gun for money to keep drinking, and the police finally picked him up for pissing in the street. Pretty soon he was back inside serving the rest of his sentence and a little extra for the gas station job.

And the moral of this story, according to Johnnie Larch, was this: don’t piss off people who work in airports.

“Are you sure it’s not something like ‘kinds of behavior that work in a specialized environment, such as a prison, can fail to work and in fact become harmful when used outside such an environment’?” said Shadow, when Johnnie Larch told him the story.

“No, listen to me, I’m telling you, man,” said Johnnie Larch, “don’t piss off those bitches in airports.”

Shadow half-smiled at the memory. His own driver’s license had several months still to go before it expired.

“Bus station! Everybody out!”

The building stank of piss and sour beer. Shadow climbed into a taxi and told the driver to take him to the airport. He told him that there was an extra five dollars if he could do it in silence. They made it in twenty minutes and the driver never said a word.

Then Shadow was stumbling through the brightly lit airport terminal. Shadow worried about the whole e-ticket business. He knew he had a ticket for a flight on Friday, but he didn’t know if it would work today. Anything electronic seemed fundamentally magical to Shadow, and liable to evaporate at any moment. He liked things he could hold and touch.

Still, he had his wallet, back in his possession for the first time in three years, containing several expired credit cards and one Visa card which, he was pleasantly surprised to discover, didn’t expire until the end of January. He had a reservation number. And, he realized, he had the certainty that once he got home everything would, somehow, be right once more. Laura would be fine again. Maybe it was some kind of scam to spring him a few days early. Or perhaps it was a simple mix-up: some other Laura Moon’s body had been dragged from the highway wreckage.

Lightning flickered outside the airport, through the windows-walls. Shadow realized he was holding his breath, waiting for something. A distant boom of thunder. He exhaled.

A tired white woman stared at him from behind the counter.

“Hello,” said Shadow. You’re the first strange woman I’ve spoken to, in the flesh, in three years. “I’ve got an e-ticket number. I was supposed to be traveling on Friday but I have to go today. There was a death in my family.”

“Mm. I’m sorry to hear that.” She tapped at the keyboard, stared at the screen, tapped again. “No problem. I’ve put you on the three thirty. It may be delayed, because of the storm, so keep an eye on the screens. Checking any baggage?”

He held up a shoulder bag. “I don’t need to check this, do I?” “No,” she said. “It’s fine. Do you have any picture ID?” Shadow showed her his driver’s license. Then he assured her that no one had given him a bomb to take onto the plane, and she, in return, gave him a printed boarding pass. Then he passed through the metal detector while his bag went through the X-ray machine.

It was not a big airport, but the number of people wandering, just wandering, amazed him. He watched people put down bags casually, observed wallets stuffed into back pockets, saw purses put down, unwatched, under chairs. That was when he realized he was no longer in prison.

Thirty minutes to wait until boarding. Shadow bought a slice of pizza and burned his lip on the hot cheese. He took his change and went to the phones. Called Robbie at the Muscle Farm, but the machine answered.

“Hey, Robbie,” said Shadow. “They tell me that Laura’s dead. They let me out early. I’m coming home.”

Then, because people do make mistakes, he’d seen it happen, he called home, and listened to Laura’s voice.

“Hi,” she said. “I’m not here or I can’t come to the phone. Leave a message and I’ll get back to you. And have a good day.”

Shadow couldn’t bring himself to leave a message.

He sat in a plastic chair by the gate, and held his bag so tight he hurt his hand.

He was thinking about the first time he had ever seen Laura. He hadn’t even known her name then. She was Audrey Burton’s friend. He had been sitting with Robbie in a booth at Chi-Chi’s, talking about something, probably how one of the other trainers had just announced she was opening her own dance studio, when Laura had walked in a pace or so behind Audrey, and Shadow had found himself staring. She had long, chestnut hair and eyes so blue Shadow mistakenly thought she was wearing tinted contact lenses. She had ordered a strawberry daiquiri, and insisted that Shadow taste it, and laughed delightedly when he did.

Laura loved people to taste what she tasted.

He had kissed her good night, that night, and she had tasted of strawberry daiquiris, and he had never wanted to kiss anyone else again. A woman announced that his plane was boarding, and Shadow’s row was the first to be called. He was in the very back, an empty seat beside him. The rain pattered continually against the side of the plane: he imagined small children tossing down dried peas by the handful from the skies.

As the plane took off he fell asleep.

Shadow was in a dark place, and the thing staring at him wore a buffalo’s head, rank and furry with huge wet eyes. Its body was a man’s body, oiled and slick.

“Changes are coming,” said the buffalo without moving its lips. “There are certain decisions that will have to be made.”

Firelight flickered from wet cave walls.

“Where am I?” Shadow asked.

“In the earth and under the earth,” said the buffalo man. “You are where the forgotten wait.” His eyes were liquid black marbles, and his voice was a rumble from beneath the world. He smelled like wet cow. “Believe,” said the rumbling voice. “If you are to survive, you must believe.”

“Believe what?” asked Shadow. “What should I believe?”

He stared at Shadow, the buffalo man, and he drew himself up huge, and his eyes filled with fire. He opened his spit-flecked buffalo mouth and it was red inside with the flames that burned inside him, under the earth.

“Everything,” roared the buffalo man.

The world tipped and spun, and Shadow was on the plane once more; but the tipping continued. In the front of the plane a woman screamed, half-heartedly.

Lightning burst in blinding flashes around the plane. The captain came on the intercom to tell them that he was going to try and gain some altitude, to get away from the storm.

The plane shook and shuddered, and Shadow wondered, coldly and idly, if he was going to die. It seemed possible, he decided, but unlikely. He stared out of the window and watched the lightning illuminate the horizon.

Then he dozed once more, and dreamed he was back in prison, and Low Key had whispered to him in the food line that someone had put out a contract on his life, but that Shadow could not find out who or why; and when he woke up they were coming in for a landing.

He stumbled off the plane, blinking and waking.

All airports, he had long ago decided, look very much the same. It doesn’t actually matter where you are, you are in an airport: tiles and walkways and restrooms, gates and newsstands and fluorescent lights. This airport looked like an airport. The trouble is, this wasn’t the airport he was going to. This was a big airport, with way too many people, and way too many gates.

The people had the glazed, beaten look you only see in airports and prisons. If Hell is other people, thought Shadow, then Purgatory is airports.

“Excuse me, ma’am?”

The woman looked at him over the clipboard. “Yes?”

“What airport is this?” She looked at him, puzzled, trying to decide whether or not he was joking, then she said, “St. Louis.”

“I thought this was the plane to Eagle Point.”

“It was. They redirected it here because of the storms. Didn’t they make an announcement?”

“Probably. I fell asleep.”

“You’ll need to talk to that man over there, in the red coat.” The man was almost as tall as Shadow: he looked like the father from a seventies sitcom, and he tapped something into a computer and told Shadow to run—run!—to a gate on the far side of the terminal.

Shadow ran through the airport, but the doors were already closed when he got to the gate. He watched the plane pull away from the gate, through the plate glass. Then he explained his problem to the gate attendant (calmly, quietly, politely) and she sent him to a passenger assistance desk, where Shadow explained that he was on his way home after a long absence and his wife had just been killed in a road accident, and that it was vitally important that he went home now. He said nothing about prison.

The woman at the passenger assistance desk (short and brown, with a mole on the side of her nose) consulted with another woman and made a phone call (“Nope, that one’s out. They’ve just cancelled it”) then she printed out another boarding card. “This will get you there,” she told him. “We’ll call ahead to the gate and tell them you’re coming.”

Shadow felt like a pea being flicked between three cups, or a card being shuffled through a deck. Again he ran through the airport, ending up near where he had gotten off in the first place.

A small man at the gate took his boarding pass. “We’ve been waiting for you,” he confided, tearing off the stub of the boarding pass, with Shadow’s seat assignment—17-D—on it. Shadow hurried onto the plane, and they closed the door behind him.

He walked through first class—there were only four first-class seats, three of which were occupied. The bearded man in a pale suit seated next to the unoccupied seat at the very front grinned at Shadow as he got onto the plane, then raised his wrist and tapped his watch as Shadow walked past.

Yeah, yeah, I’m making you late, thought Shadow. Let that be the worst of your worries.

The plane seemed pretty full, as he made his way down toward the back. Actually, Shadow quickly discovered, it was completely full, and there was a middle-aged woman sitting in seat 17-D. Shadow showed her his boarding card stub, and she showed him hers: they matched.

“Can you take your seat, please?” asked the flight attendant.

“No,” he said, “I’m afraid I can’t. This lady is sitting in it.”

She clicked her tongue and checked their boarding cards, then she led him back up to the front of the plane, and pointed him to the empty seat in first class. “Looks like it’s your lucky day,” she told him.

Shadow sat down. “Can I bring you something to drink?” she asked him. “We’ll just have time before we take off. And I’m sure you need one after that.”

“I’d like a beer, please,” said Shadow. “Whatever you’ve got.”

The flight attendant went away.

The man in the pale suit in the seat beside Shadow put out his arm and tapped his watch with his fingernail. It was a black Rolex. “You’re late,” said the man, and he grinned a huge grin with no warmth in it at all.

“Sorry?”

“I said, you’re late.”

The flight attendant handed Shadow a glass of beer. He sipped it. For one moment, he wondered if the man was crazy, and then he decided he must have been referring to the plane, waiting for one last passenger.

“Sorry if I held you up,” he said, politely. “You in a hurry?”

The plane backed away from the gate. The flight attendant came back and took away Shadow’s beer, half-finished. The man in the pale suit grinned at her and said, “Don’t worry, I’ll hold on to this tightly,” and she let him keep his glass of Jack Daniel’s, while protesting, weakly, that it violated airline regulations. (“Let me be the judge of that, m’dear.”)

“Time is certainly of the essence,” said the man. “But no, I am not in a hurry. I was merely concerned that you would not make the plane.”

“That was kind of you.”

The plane sat restlessly on the ground, engines throbbing, aching to be off.

“Kind my ass,” said the man in the pale suit. “I’ve got a job for you, Shadow.”

A roar of engines. The little plane jerked forward into a take-off, pushing Shadow back into his seat. Then they were airborne, and the airport lights were falling away below them. Shadow looked at the man in the seat next to him.

His hair was a reddish-gray; his beard, little more than stubble, was grayish-red. He was smaller than Shadow, but he seemed to take up a hell of a lot of room. A craggy, square face with pale gray eyes. The suit looked expensive, and was the color of melted vanilla ice cream. His tie was dark gray silk, and the tiepin was a tree, worked in silver: trunk, branches, and deep roots.

He held his glass of Jack Daniel’s as they took off, and did not spill a drop.

“Aren’t you going to ask me what kind of job?”

“How do you know who I am?”

The man chuckled. “Oh, it’s the easiest thing in the world to know what people call themselves. A little thought, a little luck, a little memory. Ask me what kind of job.”

“No,” said Shadow. The attendant brought him another glass of beer, and he sipped at it.

“Why not?”

“I’m going home. I’ve got a job waiting for me there. I don’t want any other job.”

The man’s craggy smile did not change, outwardly, but now he seemed, actually, amused. “You don’t have a job waiting for you at home,” he said. “You have nothing waiting for you there. Meanwhile, I am offering you a perfectly legal job—good money, limited security, remarkable fringe benefits. Hell, if you live that long, I could throw in a pension plan. You think maybe you’d like one of them?”

Shadow said, “You could have seen my name on my boarding pass. Or on the side of my bag.”

The man said nothing.

“Whoever you are,” said Shadow, “you couldn’t have known I was going to be on this plane. I didn’t know I was going to be on this plane, and if my plane hadn’t been diverted to St. Louis, I wouldn’t have been. My guess is you’re a practical joker. Maybe you’re hustling something. But I think maybe we’ll have a better time if we end this conversation here.”

The man shrugged.

Shadow picked up the in-flight magazine. The little plane jerked and bumped through the sky, making it harder to concentrate. The words floated through his mind like soap bubbles, there as he read them, gone completely a moment later.

The man sat quietly in the seat beside him, sipping his Jack Daniel’s. His eyes were closed.

Shadow read the list of in-flight music channels available on transatlantic flights, and then he was looking at the map of the world with red lines on it that showed where the airline flew. Then he had finished reading the magazine, and, reluctantly, he closed the cover, and slipped it into the pocket on the wall.

The man opened his eyes. There was something strange about his eyes, Shadow thought. One of them was a darker gray than the other. He looked at Shadow. “By the way,” he said, “I was sorry to hear about your wife, Shadow. A great loss.”

Shadow nearly hit the man, then. Instead he took a deep breath. (“Like I said, don’t piss off those bitches in airports,” said Johnnie Larch, in the back of his mind, “or they’ll haul your sorry ass back here before you can spit.”) He counted to five.

“So was I,” he said.

The man shook his head. “If it could but have been any other way,” he said, and sighed.

“She died in a car crash,” said Shadow. “It’s a fast way to go. Other ways could have been worse.”

The man shook his head, slowly. For a moment it seemed to Shadow as if the man was insubstantial; as if the plane had suddenly become more real, while his neighbor had become less so.

“Shadow,” he said. “It’s not a joke. It’s not a trick. I can pay you better than any other job you’ll find will pay you. You’re an ex-con. There’s not a long line of people elbowing each other out of the way to hire you.”

“Mister whoever-the-fuck-you-are,” said Shadow, just loud enough to be heard over the din of the engines, “there isn’t enough money in the world.”

The grin got bigger. Shadow found himself remembering a PBS show he had seen as a teenager, about chimpanzees. The show claimed that when apes and chimps smile it’s only to bare their teeth in a grimace of hate or aggression or terror. When a chimp grins, it’s a threat. This grin was one of those.

“Sure there’s money enough. And there are also bonuses. Work for me, and I’ll tell you things. There may be a little risk, of course, but if you survive you can have whatever your heart desires. You could be the next king of America. Now,” said the man, “who else is going to pay you that well? Hmm?”

“Who are you?” asked Shadow.

“Ah, yes. The age of information—young lady, could you pour me another glass of Jack Daniel’s? Easy on the ice—not, of course, that there has ever been any other kind of age. Information and knowledge: these are currencies that have never gone out of style.”

“I said, who are you?”

“Let’s see. Well, seeing that today certainly is my day—why don’t you call me Wednesday? Mister Wednesday. Although given the weather, it might as well be Thursday, eh?”

“What’s your real name?”

“Work for me long enough and well enough,” said the man in the pale suit, “and I may even tell you that. There. Job offer. Think about it. No one expects you to say yes immediately, not knowing whether you’re leaping into a piranha tank or a pit of bears. Take your time.” He closed his eyes and leaned back in his seat.

“I don’t think so,” said Shadow. “I don’t like you. I don’t want to work with you.”

“Like I say,” said the man, without opening his eyes, “don’t rush into it. Take your time.”

The plane landed with a bump, and a few passengers got off. Shadow looked out of the window: it was a little airport in the middle of nowhere, and there were still two little airports to go before Eagle Point. Shadow transferred his glance to the man in the pale suit—Mr. Wednesday? He seemed to be asleep.

Shadow stood up, grabbed his bag, and stepped off the plane, down the steps onto the slick wet tarmac, walking at an even pace toward the lights of the terminal. A light rain spattered his face.

Before he went inside the airport building, he stopped, and turned, and watched. No one else got off the plane. The ground crew rolled the steps away, the door was closed, and it taxied off down the runway. Shadow stared at it until it took off, then he walked inside, to the Budget car rental desk, the only one open, and he rented what turned out, when he got to the parking lot, to be a small red Toyota.

Shadow unfolded the map they had given him. He spread it out on the passenger’s seat. Eagle Point was about two hundred and fifty miles away, most of the journey on the freeway. He had not driven a car in three years.

The storms had passed, if they had come this far. It was cold and clear. Clouds scudded in front of the moon, and for a moment Shadow could not be certain whether it was the clouds or the moon that was moving.

He drove north for an hour and a half.

It was getting late. He was hungry, and when he realized how hungry he really was, he pulled off at the next exit, and drove into the town of Nottamun (pop. 1,301). He filled the gas-tank at the Amoco, and asked the bored woman at the cash register where the best bar in the area was—somewhere that he could get something to eat.

“Jack’s Crocodile Bar,” she told him. “It’s west on County Road N.”

“Crocodile Bar?”

“Yeah. Jack says they add character.” She drew him a map on the back of a mauve flyer, which advertised a chicken roast to raise money for a young girl who needed a new kidney. “He’s got a couple of crocodiles, a snake, one a them big lizard things.”

“An iguana?”

“That’s him.”

Through the town, over a bridge, on for a couple of miles, and he stopped at a low, rectangular building with an illuminated Pabst sign, and a Coca-Cola machine by the door.

The parking lot was half-empty. Shadow parked the red Toyota and went inside.

The air was thick with smoke and “Walkin’ after Midnight” was playing on the jukebox. Shadow looked around for the crocodiles, but could not see them. He wondered if the woman in the gas station had been pulling his leg.

“What’ll it be?” asked the bartender.

“You Jack?”

“It’s Jack’s night off. I’m Paul.”

“Hi, Paul. House beer, and a hamburger with all the trimmings. No fries.”

“Bowl of chili to start? Best chili in the state.”

“Sounds good,” said Shadow. “Where’s the restroom?”

The man pointed to a door in the corner of the bar. There was a stuffed alligator head mounted on the door. Shadow went through the door.

It was a clean, well-lit restroom. Shadow looked around the room first; force of habit. (“Remember, Shadow, you can’t fight back when you’re pissing,” Low Key said, low-key as always, in the back of his head.) He took the urinal stall on the left. Then he unzipped his fly and pissed for an age, relaxing, feeling relief. He read the yellowing press clipping framed at eye-level, with a photo of Jack and two alligators.

There was a polite grunt from the urinal immediately to his right, although he had heard nobody come in.

The man in the pale suit was bigger standing than he had seemed sitting on the plane beside Shadow. He was almost Shadow’s height, and Shadow was a big man. He was staring ahead of him. He finished pissing, shook off the last few drops, and zipped himself up.

Then he grinned, like a fox eating shit from a barbed wire fence. “So,” said Mr. Wednesday. “You’ve had time to think, Shadow. Do you want a job?”

Somewhere in America

Los Angeles. 11:26 p.m.

In a dark red room—the color of the walls is close to that of raw liver—is a tall woman dressed cartoonishly in too-tight silk shorts, her breasts pulled up and pushed forward by the yellow blouse tied beneath them. Her black hair is piled high and knotted on top of her head. Standing beside her is a short man wearing an olive T-shirt and expensive blue jeans. He is holding, in his right hand, a wallet and a Nokia mobile phone with a red, white, and blue face-plate.

The red room contains a bed, upon which are white satin-style sheets and an ox-blood bedspread. At the foot of the bed is a small wooden table, upon which is a small stone statue of a woman with enormous hips, and a candleholder.

The woman hands the man a small red candle. “Here,” she says. “Light it.”

“Me?”

“Yes,” she says, “if you want to have me.”

“I shoulda just got you to suck me off in the car.”

“Perhaps,” she says. “Don’t you want me?” Her hand runs up her body from thigh to breast, a gesture of presentation, as if she were demonstrating a new product.

Red silk scarves over the lamp in the corner of the room make the light red.

The man looks at her hungrily, then he takes the candle from her and pushes it into the candleholder. “You got a light?”

She passes him a book of matches. He tears off a match, lights the wick: it flickers and then burns with a steady flame, which gives the illusion of motion to the faceless statue beside it, all hips and breasts. “Put the money beneath the statue.”

“Fifty bucks.”

“Yes.”

“When I saw you first, on Sunset, I almost thought you were a man.”

“But I have these,” she says, unknotting the yellow blouse, freeing her breasts.

“So do a lot of guys, these days.”

She stretches and smiles. “Yes,” she says. “Now, come love me.”

He unbuttons his blue jeans, and removes his olive T-shirt. She massages his white shoulders with her brown fingers; then she turns him over, and begins to make love to him with her hands, and her fingers, and her tongue.

It seems to him that the lights in the red room have been dimmed, and the sole illumination comes from the candle, which burns with a bright flame.

“What’s your name?” he asks her.

“Bilquis,” she tells him, raising her head. “With a Q.”

“A what?”

“Never mind.”

He is gasping now. “Let me fuck you,” he says. “I have to fuck you.”

“Okay, hon,” she says. “We’ll do it. But will you do something for me, while you’re doing it?”

“Hey,” he says, suddenly tetchy, “I’m paying you, you know.”

She straddles him, in one smooth movement, whispering, “I know, honey, I know, you’re paying me, and I mean, look at you, I should be paying you, I’m so lucky . . .”

He purses his lips, trying to show that her hooker talk is having no effect on him, he can’t be taken; that she’s a street whore for Chrissakes, while he’s practically a producer, and he knows all about last-minute ripoffs, but she doesn’t ask for money. Instead she says, “Honey, while you’re giving it to me, while you’re pushing that big hard thing inside of me, will you worship me?”

“Will I what?”

She is rocking back and forth on him: the engorged head of his penis is being rubbed against the wet lips of her vulva.

“Will you call me goddess? Will you pray to me? Will you worship me with your body?”

He smiles. Is that what she wants? “Sure,” he says. We’ve all got our kinks, at the end of the day. She reaches her hand between her legs and slips him inside her.

“Is that good, is it, goddess?” he asks, gasping.

“Worship me, honey,” says Bilquis, the hooker.

“Yes,” he says. “I worship your breasts and your eyes and your cunt. I worship your thighs and your eyes and your cherry-red lips . . .”

“Yes . . . ,” she croons, riding him like a storm-tossed boat rides the waves.

“I worship your nipples, from which the milk of life flows. Your kiss is honey and your touch scorches like fire, and I worship it.” His words are becoming more rhythmic now, keeping pace with the thrust and roll of their bodies. “Bring me your lust in the morning, and bring me relief and your blessing in the evening. Let me walk in dark places unharmed and let me come to you once more and sleep beside you and make love with you again. I worship you with everything that is within me, and everything inside my mind, with everywhere I’ve been and my dreams and my . . .” He breaks off, panting for breath. “ . . . What are you doing? That feels amazing. So amazing . . .” And he looks down at his hips, at the place where the two of them conjoin, but her forefinger touches his chin and pushes his head back, so he is looking only at her face and at the ceiling once again.

“Keep talking, honey,” she says. “Don’t stop. Doesn’t it feel good?”

“It feels better than anything has ever felt,” he tells her, meaning it as he says it. “Your eyes are stars, burning in the, shit, the firmament, and your lips are gentle waves that lick the sand, and I wworship them,” and now he’s thrusting deeper and deeper inside her: he feels electric, as if his whole lower body has become sexually charged: priapic, engorged, blissful.

“Bring me your gift,” he mutters, no longer knowing what he is saying, “your one true gift, and make me always this . . . always so . . . I pray . . . I . . .”

And then the pleasure crests into orgasm, blasting his mind into void, his head and self and entire beingness a perfect blank as he thrusts deeper into her and deeper still . . .

Eyes closed, spasming, he luxuriates in the moment; and then he feels a lurch, and it seems to him that he is hanging, head-down, although the pleasure continues.

He opens his eyes.

He thinks, grasping for thought and reason again, of birth, and wonders, without fear, in a moment of perfect postcoital clarity, whether what he sees is some kind of illusion.

This is what he sees:

He is inside her to the chest, and as he stares at this in disbelief and wonder she rests both hands upon his shoulders and puts gentle pressure on his body.

He slipslides further inside her.

“How are you doing this to me?” he asks, or he thinks he asks, but perhaps it is only in his head.

“You’re doing it, honey,” she whispers. He feels the lips of her vulva tight around his upper chest and back, constricting and enveloping him. He wonders what this would look like to somebody watching them. He wonders why he is not scared. And then he knows.

“I worship you with my body,” he whispers, as she pushes him inside her. Her labia pull slickly across his face, and his eyes slip into darkness.

She stretches on the bed, like a huge cat, and then she yawns. “Yes,” she says, “You do.”

The Nokia phone plays a high, electrical transposition of the “Ode to Joy.” She picks it up, and thumbs a key, and puts the telephone to her ear.

Her belly is flat, her labia small and closed. A sheen of sweat glistens on her forehead and on her upper lip.

“Yeah?” she says. And then she says, “No, honey, he’s not here. He’s gone away.” She turns the telephone off before she flops out on the bed in the dark red room, then she stretches once more, and she closes her eyes, and she sleeps.

Chapter Two

They took her to the cemet’ry

In a big ol’ Cadillac

They took her to the cemet’ry

But they did not bring her back.

—old song

Ihave taken the liberty,” said Mr. Wednesday, washing his hands in the men’s room of Jack’s Crocodile Bar, “of ordering food for myself, to be delivered to your table. We have much to discuss, after all.”

“I don’t think so,” said Shadow. He dried his own hands on a paper towel and crumpled it, and dropped it into the bin.

“You need a job,” said Wednesday. “People don’t hire ex-cons. You folk make them uncomfortable.”

“I have a job waiting. A good job.”

“Would that be the job at the Muscle Farm?”

“Maybe,” said Shadow.

“Nope. You don’t. Robbie Burton’s dead. Without him the Muscle Farm’s dead too.”

“You’re a liar.”

“Of course. And a good one. The best you will ever meet. But, I’m afraid, I’m not lying to you about this.” He reached into his pocket, produced a newspaper, much folded, and handed it to Shadow. “Page seven,” he said. “Come on back to the bar. You can read it at the table.”

Shadow pushed open the door, back into the bar. The air was blue with smoke, and the Dixie Cups were on the jukebox singing “Iko Iko.” Shadow smiled, slightly, in recognition of the old children’s song.

The barman pointed to a table in the corner. There was a bowl of chili and a burger at one side of the table, a rare steak and a bowl of fries laid in the place across from it.

Look at my King all dressed in Red,

Iko Iko all day,

I bet you five dollars he’ll kill you dead,

Jockamo-feena-nay

Shadow took his seat at the table. He put the newspaper down. “I got out of prison this morning,” he said. “This is my first meal as a free man. You won’t object if I wait until after I’ve eaten to read your page seven?”

“Not in the slightest bit.”

Shadow ate his hamburger. It was better than prison hamburgers. The chili was good but, he decided, after a couple of mouthfuls, not the best in the state.

Laura made a great chili. She used lean-cut meat, dark kidney beans, carrots cut small, a bottle or so of dark beer, and freshly sliced hot peppers. She would let the chili cook for a while, then add red wine, lemon juice, and a pinch of fresh dill, and, finally, measure out and add her chili powders. On more than one occasion Shadow had tried to get her to show him how she made it: he would watch everything she did, from slicing the onions and dropping them into the olive oil at the bottom of the pot on. He had even written down the sequence of events, ingredient by ingredient, and he had once made Laura’s chili for himself on a weekend when she had been out of town. It had tasted okay—it was certainly edible, and he ate it, but it had not been Laura’s chili.

The news item on page seven was the first account of his wife’s death that Shadow had read. It felt strange, as if he were reading about someone in a story: how Laura Moon, whose age was given in the article as twenty-seven, and Robbie Burton, thirty-nine, were in Robbie’s car on the interstate, when they swerved into the path of a thirty-two wheeler, which sideswiped them as it tried to change lanes and avoid them. The truck brushed Robbie’s car and sent it spinning off the side of the road, where the car had hit a road sign, hard, and stopped spinning.

Rescue crews were on the scene in minutes. They pulled Robbie and Laura from the wreckage. They were both dead by the time they arrived at the hospital.

Shadow folded the newspaper up once more, and slid it back across the table, toward Wednesday, who was gorging himself on a steak so bloody and so blue it might never have been introduced to a kitchen flame.

“Here. Take it back,” said Shadow.

Robbie had been driving. He must have been drunk, although the newspaper account said nothing about this. Shadow found himself imagining Laura’s face when she realized that Robbie was too drunk to drive. The scenario unfolded in Shadow’s mind, and there was nothing he could do to stop it: Laura shouting at Robbie—shouting at him to pull off the road, then the thud of car against truck, and the steering wheel wrenching over . . .

. . . the car on the side of the road, broken glass glittering like ice and diamonds in the headlights, blood pooling in rubies on the road beside them. Two bodies, dead or soon-to-die, being carried from the wreck, or laid neatly by the side of the road.

“Well?” asked Mr. Wednesday. He had finished his steak, sliced and devoured it like a starving man. Now he was munching the french fries, spearing them with his fork.

“You’re right,” said Shadow. “I don’t have a job.”

Shadow took a quarter from his pocket, tails up. He flicked it up in the air, knocking it against his finger as it left his hand to give it a wobble that made it look as if it were turning, caught it, slapped it down on the back of his hand.

“Call,” he said.

“Why?” asked Wednesday.

“I don’t want to work for anyone with worse luck than me. Call.”

“Heads,” said Mr. Wednesday.

“Sorry,” said Shadow, revealing the coin without even bothering to glance at it. “It was tails. I rigged the toss.”

“Rigged games are the easiest ones to beat,” said Wednesday, wagging a square finger at Shadow. “Take another look at the quarter.”

Shadow glanced down at it. The head was face-up.

“I must have fumbled the toss,” he said, puzzled.

“You do yourself a disservice,” said Wednesday, and he grinned. “I’m just a lucky, lucky guy.” Then he looked up. “Well I never. Mad Sweeney. Will you have a drink with us?”

“Southern Comfort and Coke, straight up,” said a voice from behind Shadow.

“I’ll go and talk to the barman,” said Wednesday. He stood up, and began to make his way toward the bar.

“Aren’t you going to ask what I’m drinking?” called Shadow.

“I already know what you’re drinking,” said Wednesday, and then he was standing by the bar. Patsy Cline started to sing “Walkin’ after Midnight” on the jukebox again.

The man who had ordered Southern Comfort and Coke sat down beside Shadow. He had a short ginger-colored beard. He wore a denim jacket covered with bright sew-on patches, and under the jacket a stained white T-shirt. On the T-shirt was printed:

IF YOU CAN’T EAT IT. DRINK IT. SMOKE IT OR SNORT IT . . . THEN F*CK IT!

He wore a baseball cap, on which was printed:

THE ONLY WOMAN I HAVE EVER LOVED

WAS ANOTHER MAN’S WIFE . . .

MY MOTHER!

He opened a soft pack of Lucky Strikes with a dirty thumbnail, took a cigarette, offered one to Shadow. Shadow was about to take one, automatically—he did not smoke, but a cigarette makes good barter material—when he realized that he was no longer inside. You could buy cigarettes here whenever you wanted. He shook his head.

“You working for our man then?” asked the bearded man. He was not sober, although he was not yet drunk.

“It looks that way,” said Shadow.

The bearded man lit his cigarette. “I’m a leprechaun,” he said.

Shadow did not smile. “Really?” he said. “Shouldn’t you be drinking Guinness?”

“Stereotypes. You have to learn to think outside the box,” said the bearded man. “There’s a lot more to Ireland than Guinness.”

“You don’t have an Irish accent.”

“I’ve been over here too fucken long.”

“So you are originally from Ireland?”

“I told you. I’m a leprechaun. We don’t come from fucken Moscow.”

“I guess not.”

Wednesday returned to the table, three drinks held easily in his paw-like hands. “Southern Comfort and Coke for you, Mad Sweeney, m’man, and a Jack Daniel’s for me. And this is for you, Shadow.”

“What is it?”

“Taste it.”

The drink was a tawny golden color. Shadow took a sip, tasting an odd blend of sour and sweet on his tongue. He could taste the alcohol underneath, and a strange blend of flavors. It reminded him a little of prison hooch, brewed in a garbage bag from rotten fruit and bread and sugar and water, but it was smoother, sweeter, infinitely stranger.

“Okay,” said Shadow. “I tasted it. What was it?”

“Mead,” said Wednesday. “Honey wine. The drink of heroes. The drink of the gods.”

Shadow took another tentative sip. Yes, he could taste the honey, he decided. That was one of the tastes. “Tastes kinda like pickle juice,” he said. “Sweet pickle juice wine.”

“Tastes like a drunken diabetic’s piss,” agreed Wednesday. “I hate the stuff.”

“Then why did you bring it for me?” asked Shadow, reasonably.

Wednesday stared at Shadow with his mismatched eyes. One of them, Shadow decided, was a glass eye, but he could not decide which one. “I brought you mead to drink because it’s traditional. And right now we need all the tradition we can get. It seals our bargain.”

“We haven’t made a bargain.”

“Sure we have. You work for me. You protect me. You help me. You transport me from place to place. You investigate, from time to time—go places and ask questions for me. You run errands. In an emergency, but only in an emergency, you hurt people who need to be hurt. In the unlikely event of my death, you will hold my vigil. And in return I shall make sure that your needs are adequately taken care of.”

“He’s hustling you,” said Mad Sweeney, rubbing his bristly ginger beard. “He’s a hustler.”

“Damn straight I’m a hustler,” said Wednesday. “That’s why I need someone to look out for my best interests.”

The song on the jukebox ended, and for a moment the bar fell quiet, every conversation at a lull.

“Someone once told me that you only get those everybody-shuts-up-at-once moments at twenty past or twenty to the hour,” said Shadow.

Sweeney pointed to the clock above the bar, held in the massive and indifferent jaws of a stuffed alligator head. The time was 11:20.

“There,” said Shadow. “Damned if I know why that happens.”

“I know why,” said Wednesday.

“You going to share with the group?”

“I may tell you, one day, yes. Or I may not. Drink your mead.”

Shadow knocked the rest of the mead back in one long gulp. “It might be better over ice,” he said.

“Or it might not,” said Wednesday. “It’s terrible stuff.”

“That it is,” agreed Mad Sweeney. “You’ll excuse me for a moment, gentlemen, but I find myself in deep and urgent need of a lengthy piss.” He stood up and walked away, an impossibly tall man. He had to be almost seven feet tall, decided Shadow.

A waitress wiped a cloth across the table and took their empty plates. She emptied Sweeney’s ashtray, and asked if they would like to order any more drinks. Wednesday told her to bring the same again for everyone, although this time Shadow’s mead was to be on the rocks. “Anyway,” said Wednesday, “that’s what I need of you, if you’re working for me. Which, of course, you are.”

“That’s what you want,” said Shadow. “Would you like to know what I want?”

“Nothing could make me happier.”

The waitress brought the drink. Shadow sipped his mead on the rocks. The ice did not help—if anything it sharpened the sourness, and made the taste linger in the mouth after the mead was swallowed. However, Shadow consoled himself, it did not taste particularly alcoholic. He was not ready to be drunk. Not yet.

He took a deep breath.

“Okay,” said Shadow. “My life, which for three years has been a long way from being the greatest life there has ever been, just took a distinct and sudden turn for the worse. Now there are a few things I need to do. I want to go to Laura’s funeral. I want to say goodbye. After that, if you still need me, I want to start at five hundred dollars a week.” The figure was a stab in the dark, a made-up number. Wednesday’s eyes revealed nothing. “If we’re happy working together, in six months’ time you raise it to a thousand a week.”

He paused. It was the longest speech he’d made in years. “You say you may need people to be hurt. Well, I’ll hurt people if they’re trying to hurt you. But I don’t hurt people for fun or for profit. I won’t go back to prison. Once was enough.”

“You won’t have to,” said Wednesday.

“No,” said Shadow. “I won’t.” He finished the last of the mead. He wondered, suddenly, somewhere in the back of his head, whether the mead was responsible for loosening his tongue. But the words were coming out of him like the water spraying from a broken fire hydrant in summer, and he could not have stopped them if he had tried. “I don’t like you, Mister Wednesday, or whatever your real name may be. We are not friends. I don’t know how you got off that plane without me seeing you, or how you trailed me here. But I’m impressed. You have class. And I’m at a loose end right now. You should know that when we’re done, I’ll be gone. And if you piss me off, I’ll be gone too. Until then, I’ll work for you.”

Wednesday grinned. His smiles were strange things, Shadow decided. They contained no shred of humor, no happiness, no mirth. Wednesday looked like he had learned to smile from a manual.

“Very good,” he said. “Then we have a compact. And we are agreed.”

“What the hell,” said Shadow. Across the room, Mad Sweeney was feeding quarters into the jukebox. Wednesday spat in his hand and extended it. Shadow shrugged. He spat in his own palm. They clasped hands. Wednesday began to squeeze. Shadow squeezed back. After a few seconds his hand began to hurt. Wednesday held the grip for another half-minute, and then he let go.

“Good,” he said. “Good. Very good.” He smiled, a brief flash, and Shadow wondered if there had been real humor in that smile, actual pleasure. “So, one last glass of evil, vile fucking mead to seal our deal, and then we are done.”

“It’ll be a Southern Comfort and Coke for me,” said Sweeney, lurching back from the jukebox.

The jukebox began to play the Velvet Underground’s “Who Loves the Sun?” Shadow thought it a strange song to find on a jukebox. It seemed very unlikely. But then, this whole evening had become increasingly unlikely.

Shadow took the quarter he had used for the coin-toss from the table, enjoying the sensation of a freshly milled coin against his fingers, producing it in his right hand between forefinger and thumb. He appeared to take it into his left hand in one smooth movement, while casually fingerpalming it. He closed his left hand on the imaginary quarter. Then he took a second quarter in his right hand, between finger and thumb, and, as he pretended to drop that coin into the left hand, he let the palmed quarter fall into his right hand, striking the quarter he held there on the way. The chink confirmed the illusion that both coins were in his left hand, while they were now both held safely in his right.

“Coin tricks is it?” asked Sweeney, his chin raising, his scruffy beard bristling. “Why, if it’s coin tricks we’re doing, watch this.”

He took a glass from the table, a glass that had once held mead, and he tipped the ice-cubes into the ashtray. Then he reached out and took a large coin, golden and shining, from the air. He dropped it into the glass. He took another gold coin from the air and tossed it into the glass, where it clinked against the first. He took a coin from the candle flame of a candle on the wall, another from his beard, a third from Shadow’s empty left hand, and dropped them, one by one, into the glass. Then he curled his fingers over the glass, and blew hard, and several more golden coins dropped into the glass from his hand. He tipped the glass of sticky coins into his jacket pocket, and then tapped the pocket to show, unmistakably, that it was empty.

“There,” he said. “That’s a coin trick for you.”

Shadow, who had been watching closely throughout the impromptu performance, put his head on one side. “We have to talk about that,” he said. “I need to know how you did it.”

“I did it,” said Sweeney, with the air of one confiding a huge secret, “with panache and style. That’s how I did it.” He laughed, silently, rocking on his heels, his gappy teeth bared.

“Yes,” said Shadow. “That is how you did it. You’ve got to teach me. All the ways of doing the Miser’s Dream that I’ve read about you’d be hiding the coins in the hand that holds the glass, and dropping them in while you produce and vanish the coin in your right hand.”

“Sounds like a hell of a lot of work to me,” said Mad Sweeney. “It’s easier just to pick them out of the air.” He picked up his half-finished Southern Comfort and Coke, looked at it, and put it down on the table.

Wednesday stared at both of them as if he had just discovered new and previously unimagined life forms. Then he said, “Mead for you, Shadow. I’ll stick with Mister Jack Daniel’s, and for the freeloading Irishman . . . ?”

“A bottled beer, something dark for preference,” said Sweeney. “Freeloader, is it?” He picked up what was left of his drink, and raised it to Wednesday in a toast. “May the storm pass over us, and leave us hale and unharmed,” he said, and knocked the drink back.

“A fine toast,” said Wednesday. “But it won’t.”

Another mead was placed in front of Shadow.

“Do I have to drink this?” he asked, without enthusiasm.

“Yes, I’m afraid you do. It seals our deal. Third time’s the charm, eh?”

“Shit,” said Shadow. He swallowed the mead in two large gulps. The pickled honey taste filled his mouth.

“There,” said Mr. Wednesday. “You’re my man, now.”

“So,” said Sweeney, “you want to know the trick of how it’s done?”

“Yes,” said Shadow. “Were you loading them in your sleeve?”

“They were never in my sleeve,” said Sweeney. He chortled to himself, rocking and bouncing as if he were a lanky, bearded, drunken volcano preparing to erupt with delight at his own brilliance. “It’s the simplest trick in the world. I’ll fight you for it.”

Shadow shook his head. “I’ll pass.”

“Now there’s a fine thing,” said Sweeney to the room. “Old Wednesday gets himself a bodyguard, and the feller’s too scared to put up his fists, even.”

“I won’t fight you,” agreed Shadow.

Sweeney swayed and sweated. He fiddled with the peak of his baseball cap. Then he pulled one of his coins out of the air and placed it on the table. “Real gold, if you were wondering,” said Sweeney. “Win or lose—and you’ll lose—it’s yours if you fight me. A big fellow like you—who’d’a thought you’d be a fucken coward?”

“He’s already said he won’t fight you,” said Wednesday. “Go away, Mad Sweeney. Take your beer and leave us in peace.”

Sweeney took a step closer to Wednesday. “Call me a freeloader, will you, you doomed old creature? You cold-blooded, heartless old treehanger.” His face was turning a deep, angry red.

Wednesday put out his hands, palms up, pacific. “Foolishness, Sweeney. Watch where you put your words.”