Tor.com comics blogger Tim Callahan has dedicated the next twelve months to a reread of all of the major Alan Moore comics (and plenty of minor ones as well). Each week he will provide commentary on what he’s been reading. Welcome to the 11th installment.

In the second half of Alan Moore’s “Captain Britain” run – hopping from the final issues of The Daredevils anthology into another Marvel UK reprint-plus-new-stuff comic called The Mighty World of Marvel – the writer wraps up his most sincere superhero story with the kind of enormity that’s usually reserved for what’s called “Event” comics these days.

In “Captain Britain,” worlds live, worlds die, and nothing will ever be the same again.

But Moore was doing this immense story in eight-or-eleven-page chunks in a tiny corner of a British publication that was primarily used to push Wolverine and Micronauts stories onto innocent young readers across the Atlantic.

Last week, I referred to the first half of Moore’s run as “widescreen comics, one tiny panel at a time,” and that’s an apt description for the rest of the story as well. This story is bigger than its borders and page count. And it doesn’t attempt to do anything fancy with the superhero genre, other than push it to its extremes, with immensity of conflict, deep pathos, and a “Funeral on Otherworld.”

Let’s get into it, shall we?

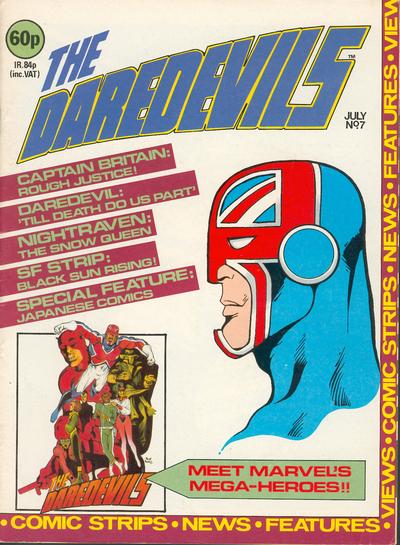

“Captain Britain,” The Daredevils #7-11 (Marvel UK, July 1983-Nov. 1983)

Alan Moore, along with Alan Davis – artist on pretty much all of these early-80s “Captain Britain” serials, before and after Alan Moore – continues to weave together the dangling plot threads from the first half of his run. In addition to the “A” plot about Saturnyne’s prosecution over the “handling of the Earth 238 disaster,” Moore layers the ominous threat of the Fury, and the nightmares of Captain U.K., the female analogue of our hero who has flashes of what will happen when James Jaspers takes charge of our Earth.

Well, I suppose it’s not really our Earth, but it’s Captain Britain’s Earth, a.k.a. Earth 616, the now-official-Earth-of-Marvel-continuity.

I always thought that the Earth 616 designation was a great joke, counter to DC’s multiversal numbering system which identified their main continuity as “Earth-1” or “New Earth.” Marvel’s primary continuity is just some random reality, nothing inherently special about it, except we happen to watch stories unfold there. It’s not immediately identified as the center of the “Omniverse,” necessarily.

Of course, there’s some dispute about who originated the “616” identifier, and a few claims by current Marvel head honchos about how much they dislike the term. As usual Wikipedia has all the facts – true or not – about the situation.

And Moore and Davis make another Marvelman/Miracleman joke in the opener here, as we see a superhero wearing a very familiar costume become vaporized by the Fury (in Captain U.K.’s flashback, or nightmare-flashforward), and the caption reads “Miracleman! It shot Miracleman!” We cut to see Captain U.K. standing in front of someone who seems to wear a Young Marvelman costume, and our female Captain Britain analogue refers to him as “Rick.” Young Marvelman, you may recall, is named Dickie Dauntless in the original series.

It’s a throwaway bit, here, but it helps demonstrate Moore and Davis’s approach to “Captain Britain.” It’s a playful approach, and while it may contain exploding universes and dead superheroes, it is never as bleak or “real” as Moore’s concurrent work with “Marvelman” or “V for Vendetta,” or his later work on Watchmen or even Swamp Thing. Not that Swamp Thing is bleak or hopeless overall – it’s actually a love story, mostly, with horror elements – but when it does shine the spotlight on costumed heroes, they don’t glimmer as brightly as they do here.

You might call Moore’s “Captain Britain” work an “energetic romp.” Try it. See how that sounds to you. It’s not quite true, but it’s close. Maybe an “energetic romp, with an underlying darkness.”

Still, since that’s kind of the recipe for most of today’s successful superhero comics – from Geoff Johns’s Green Lantern to Mark Waid’s Daredevil to Rick Remender’s Uncanny X-Force – it’s clearly an approach that readers respond to. And, unlike “Marvelman” or Watchmen, it’s a sustainable point of view. Even if Alan Moore is a perennially impossible act to follow. (Though Jamie Delano has tried.)

Back to the plot!

Captain Britain and the Special Executive fight to free Saturnyne from her unjust imprisonment-slash-prosecution. Captain U.K. – in civvies – points out that politician James Jaspers is saying the same crazy stuff on Earth 616 that led to all the chaos and superhero genocide on her Earth. And the Fury, unstoppable superhero cyborg killing machine, approaches.

Space Merlin and his daughter play cosmic chess with the characters. Like a scene out of that Harry Hamlin movie with a Xanadu-styled Laurence Olivier.

There’s also a panel, seven pages into the “Captain Britain” episode of The Daredevils#9, that seems to be a precursor to what Moore would later do in Miracleman #15 with heads on pikes and superhero super-violence. It’s a panel showing what’s in Betsy Braddock’s mind as she telepathically tunes in to what Captain U.K. is raving about. It’s a red-and-orange panel, full of shadows, with craggy superhero figures, like Spider-Man and Captain America hunched in chains, while a demonic figure stands atop a broken Captain Britain and a Betsy Braddock tortured with barbed wire around her neck.

Someone snarkier than I might say it’s a panel that has informed Mark Millar’s entire career.

It’s a powerful panel now, and in the comics world of 1983, it would have been even more shocking, I’m sure.

And by the end of that issue, the Fury looms, superhero-killing arm-cannon pointed right at the neck of the seemingly depowered, out-of-her-universe Captain U.K. It’s quite a cliff-hanger, and unlike most superhero comics, we’ve seen enough so far in Moore’s “Captain Britain” run to know that anything could happen. No one is safe.

The ensuing confrontation with the killer cyborg fills up the final two chapters of the “Captain Britain” serial in The Daredevils anthology. It’s a long fight scene, involving the Special Executive and Captain Britain taking on the unstoppable dimension-hopping monster. A piece representing the Fury even suddenly appears on space-Merlin’s game board, outside of his control. Reality is beyond the old alien wizard’s control, which comes as a surprise to him.

The Special Executive suffers losses in the battle, as Wardog loses his robot arm, and the multiple-man, Legion, is sliced in half by the Fury, killing all his duplicates in the process. We then see a double-page spread, tracing the story through the layers of reality, and showing that James Jaspers – or Mad Jim Jaspers as he was known on the other Earth – has manipulated something fundamental, the “pattern broken.” Reality is coming undone.

The heroes (and mercenaries) combine their forces to overwhelm the Fury, burying him under standard comic book rubble. Nursing their wounds, and lamenting their wounded, the Special Executive walk away, leaving Captain Britain to clean up. But the story isn’t over, even if the series housing it has come to an end. No, the “Captain Britain” saga – at least the Alan Moore version – jumps over to another anthology title….

“Captain Britain,” The Mighty World of Marvel #7-13 (Marvel UK, Dec. 1983-June 1984)

Though the next chapter of the story continued only a month after The Daredevils series ended, the in-story time jumped forward significantly. Or there was enough of a Jaspers-caused reality ripple to radically change the world. Because now there are concentration camps, Jaspers is in charge of everything, and demonically-armored thugs keep the citizens in line.

With their horned helmets and glowing eyes, they allude back to the nightmare image from Betsy Braddock’s telepathic vision. The future has come to be, and it is one of tyranny and oppression. If earlier installments made reference – even jokingly – to “Marvelman,” this is the section of the “Captain Britain” serial that trucks in the fascism of “V for Vendetta,” with our hero and his family (including the alternate-universe Captain U.K.) as the underground rebels.

Jaspers is no bureaucrat, though. He’s a cosmic madman. A Mad Hatter of spacetime, hamming it up as he shapes the world at his whim, and plays with everything in sight at the quantum level. Yet, contrasted with that horrific slapstick, we still get a sense of the underlying nobility of the conflict, and more than a little purple prose from Alan Moore. One series of captions – juxtaposed with Brian Braddock suiting up for battle in his superhero costume – reads, “It’s England…/…not that you’d ever know. / The sky is torn. The landscape is raped and raw. / The Night is curdled with nightmares. / It’s still his country.”

A patriotic monologue, spoken by an unnamed narrator, for a patriotic comic book series written by someone who has long proven himself to be far left-of-center. And it works.

Structurally, Moore folds the story back on itself in the climax, as Captain Britain confronts Jim Jaspers and characters – including the dead elf Jackdaw – reappear, baffling the direct and literal-minded superhero. He tears through reality – tearing through the comic book panels themselves – to find himself in a hospital bed with his mother caring for him. The notion of a stable reality has completely disappeared by this point. Everything is child-like chaos, with Captain Britain caught in the capricious whims of Mad Jim Jaspers. Until the Fury returns, and things get serious.

Though, and this is an important “though,” the final confrontation – turning Jaspers and the Fury against each other – is about as serious as a Bugs Bunny cartoon, or a Jack Cole comic. The entire fate of reality is at stake, but Jasper’s matter manipulation and the Fury’s unstoppability clash against each other. Their shifting forms batter each other, and, in space, Merlin dies. He cannot handle the strain of the reality-rending conflict.

In the end, the Fury defeats Jaspers, and Captain U.K. rises from the shadows of her own despondency to save Captain Britain from the cyborg killer. She kills the Fury, getting long-awaiting revenge for what the monster did to her world.

Moore ends his run with a funeral for Merlin, and a kiss between his two Captains before they walk away into the darkness. Though the caption reads “Never the End,” it is indeed the end for Alan Moore’s run on the series. He wraps up the dimension hopping story that began even before he took over, and ends everything on a satisfying emotional note.

It’s no surprise that most of my discussion of Moore’s “Captain Britain” run has focused on summarizing the plot – which I am normally disinclined to do – because this is a comic that’s built around plot first, spectacle second, character third, and stylistic innovation last. As Moore’s only sustained corporate superhero run, it occupies a unique place in his bibliography, and it certainly pulls from the best of the Mort Weisinger Superman era – in terms of absurd ideas – and the Chris Claremontian melodrama that would dominate so many comics at the time Moore’s “Captain Britain” comics were written. But it also points to the direction in which more superhero comics would eventually head. Where everything is a major crisis, the violence is excessive, and yet everything can bounce back to the way it was with a twist of the reality mending writerly wand.

Yet even within that framework, compelling stories can be told – stories that linger, even if their impact on the fictional reality leaves barely a mark. The costumes may change, characters may stay temporarily dead, but nothing really sticks in the corporate fictional universes of these superheroes. But a good story can change the reader, can show the reader what’s possible, even if nothing on the page remains altered.

And “Captain Britain” is certainly a good story. It’s almost everything you would ever want in a superhero spectacle. Even 28 years after it reached its conclusion.

NEXT TIME: Alan Moore’s Best “Future Shocks”

Tim Callahan writes about comics for Tor.com, Comic Book Resources, and Back Issue magazine. Follow him on Twitter.