The author wishes to acknowledge the significant aid of Bob Burns in providing information and photographs in the preparation of this profile. Clearly, without Bob’s indispensable assistance this article would not have been possible.

The story of monster maker Paul Blaisdell—his meteoric rise in the field of low budget motion pictures, and his equally precipitous fall from grace as trends and production methods changed—is, I’m sure, not unlike the story of scores of others who struggled to make their mark in the film business.

In Blaisdell’s case, however, there is a qualitative difference. His monsters were more outlandish and imaginative, his talents greater, his limitations of budget and time often more severe, and his hardships and ultimate undoing more devastating to a fragile ego that rightfully craved a need for greater recognition and better treatment. But to appreciate his story more fully, it is necessary to also understand, to some degree, the odd, out of kilter world of low budget filmmaking of the ’50s and ’60s and the men and women who made them.

The involvement of independent and small studio filmmakers in science fiction movies goes back to the very beginnings of the motion picture itself. Georges Méliès’ Star Films facility in Montreuil, France had, for instance, been the world’s first viable movie studio, and his landmark effort A Trip to the Moon (Star Films, 1902), its first authentic science fiction picture. Through the decades leading up the boom years of the 1950s, and with the exception of Universal (and rare, yet noteworthy entries by studios like Columbia and RKO), the low-end companies—what we today refer to as the poverty row studios—largely carried the mantle of SF through the 1930s and ’40s. At the outset of the 1950s science fiction film boom, Destination Moon and Rocketship X-M—the very movies that initiated the cycle—had been modestly financed and released by small startup companies. And when the big studios lost faith in the ability of SF to attract audiences, it was again the independents who were there, ready and eager to fill the void.

One such studio, eventually to become known as American International Pictures, not only rose to the call, but also shrewdly targeted its product to youngsters, often creating motion pictures in which teenagers themselves were the protagonists. They started with SF and, soon after, horror; expanded to rock ‘n’ roll and juvenile delinquency films, headed out to the beach for the wildly popular surfer movies of teenage heartthrobs Frankie Avalon and Annette Funicello, then finished off with a run of brutal, antisocial gangster and biker flicks.

The brain trust and co-founders of this small company, originally called the American Releasing Corporation, were its president, James H. Nicholson (1916-1972), and its vice-president, Samuel Z. Arkoff (1918-2001). Nicholson was an avid film fan with experience at RealArt, a company that specialized in the re-releasing of older films; Arkoff was a shrewd lawyer and businessman from the mid-west with an uncanny knack for making money on minimal investments. At first ARC acquired older movies at little cost, relabeled them with flashy titles and outfitted them with new poster art, then re-released them. Nicholson, especially, had a flair for coming up with the most sensational and provocative of titles. The partners knew that the key to making money in the film business had little to do with quality; what mattered most was how the movies were packaged and promoted to exhibitors. Nicholson and Arkoff were also aware that although television was siphoning off older members of the movie-viewing audience, nothing could keep teenagers at home on the weekends, and that a likely point of convergence was at the local drive-in theaters. Thus, their marketing strategy centered around tapping into the interests of younger viewers and circumventing a distribution system largely predisposed to the major studios by hawking their wares to the relatively small number of independent theaters across the country and to the larger national network of drive-ins, almost all of which were privately owned.

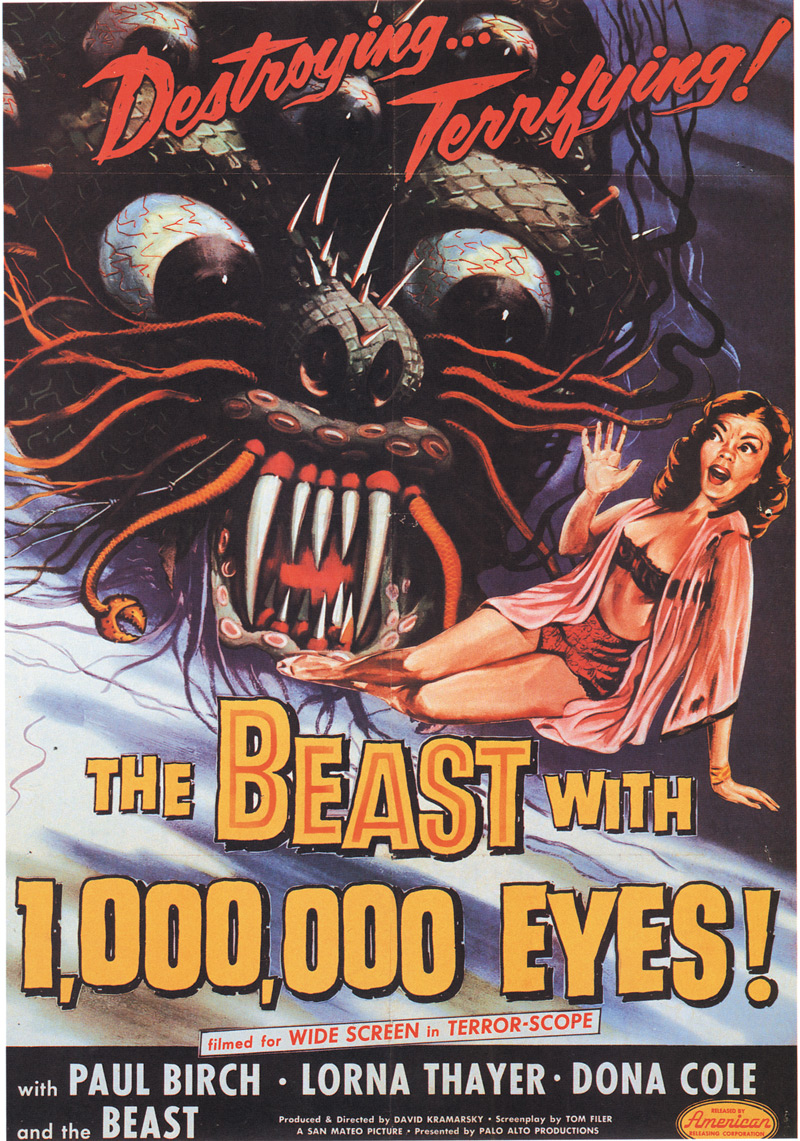

When the idea finally came to them to finance films of their own making, Nicholson usually came up with a flashy title, then art was commissioned for the poster and the movies were marketed to theater owners before the first frame of film was shot. Such was the case with The Beast with a Million Eyes (1955), ARC’s first venture into science fiction.

The name most associated with The Beast with a Million Eyes is that of Roger Corman (b. 1926), an enterprising, low budget filmmaker who a year earlier produced Wyott Ordung’s The Monster from the Ocean Floor (Lippert, 1954) for the paltry sum of twelve thousand dollars. It had been Ordung, an aspiring actor and screenwriter, who first introduced Corman to Nicholson and Arkoff while looking for a distributor for his monster picture. By the time The Beast with a Million Eyes went into production Corman had already opted to join the Directors Guild with his directorial debut in Five Guns West (ARC, 1955), and he was restricted from working directly on the new science fiction film. His participation would have necessitated union involvement, and at less than thirty thousand dollars, its slim production budget prohibited any prospect of hiring a cast and crew at union scale. Consequently, Corman assigned his production assistant, David Kramarsky, to produce and direct from a script by Tom Filer.

The central theme of Filer’s script was that an invading alien has come to Earth and is wholly without material form. The rationale for Nicholson’s flamboyant title is that the invisible alien can see through the eyes of all of Earth’s lower lifeforms to spy on humanity. Credible accounts suggest that Lou Place, Corman’s production manager, actually directed the film, but that Place had his name removed from the credits prior to its release.

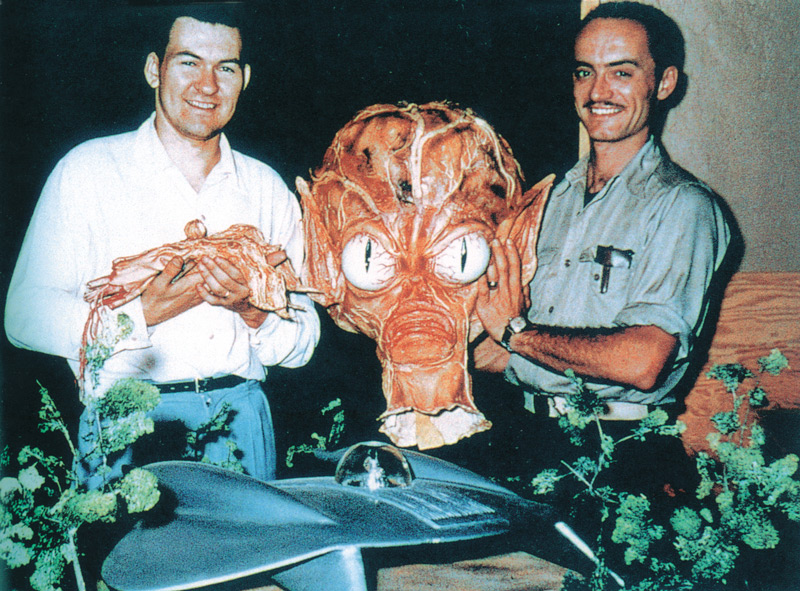

When the seventy-eight minute film was screened for eager exhibitors, they were bewildered to discover that no monster was in sight, despite the implications of Nicholson’s colorful title and poster art. Under pressure from ARC, Corman called the well-known science fiction fan, editor and literary agent, Forrest J. Ackerman (b. 1916) to enlist his aid in finding someone to make a monster on short notice and on a limited budget. Ackerman first suggested his friend, the noted stop motion animator Ray Harryhausen (Mighty Joe Young, RKO, 1949; The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms, Warner Bros, 1953; It Came from Beneath the Sea, Columbia, 1955), but Harryhausen’s services were priced well beyond Corman’s reach. Ackerman then suggested Jacques Fresco who’d worked on Project Moonbase for Lippert (1953), but Fresco was also too expensive. Finally Ackerman asked just what kind of budget Corman had in mind and the two negotiated a fee of four hundred dollars—two hundred for labor and two hundred for materials. Ackerman finally suggested illustrator Paul Blaisdell, a young artist with no film experience, but with a rich imagination and some talent for making marionettes and scratch models of vintage airplanes.

Paul Blaisdell loved science fiction and was already working as an illustrator for Bill Crawford’s SF digest, Spaceways, when he received the auspicious telephone call from Forrest J. Ackerman in the early 1950s to join his agency. Impressed with Blaisdell’s art, Ackerman began representing him and had gotten him work with Ray Palmer’s Chicago-based magazine, Other Worlds. Soon after, assignments from The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction began to materialize. With his acceptance of Corman’s offer, Blaisdell’s career entered a new phase—that of master monster maker for the low budget film industry. It would be the specialty for which he is today best remembered.

Blaisdell was born in Newport, Rhode Island on July 21, 1927 and studied art under the GI bill at the New England School of Art and Design after his discharge from the army in 1947. His closest collaborator throughout his film career was his wife Jackie who is still alive, but who has gone into seclusion since Blaisdell’s death from stomach cancer in 1983. Paul Blaisdell was not quite fifty-six when he died. Bob Burns had been a close friend from soon after Blaisdell’s first film commission in 1955, and he assisted him on some of his later films. Burns is a noted movie historian and collector, who, more than anyone, has gone to great lengths to keep Paul Blaisdell’s memory alive. I interviewed Burns, a retired film editor, by telephone on November 25, 2002 and asked him about the circumstances of his first meeting with the Blaisdells.

My wife Kathy and I went to some sort of sci-fi thing—LASFS [the Los Angeles Science Fantasy Society], or something—and Ray Bradbury was talking about his screenplay for Moby Dick [Warner Bros., 1956]; and I liked Bradbury and I liked Moby Dick, so Kathy and I were anxious to hear what he had to say. We went to this event—we normally didn’t go to these things—but we went, and we just happened to sit right next to Paul and Jackie, not knowing them at all, of course. And then they took a break and we just kind of started talking. It was just one of those things, I guess. I don’t even know how the subject got started, but we started to talk about monsters and Paul said, “Gee, I’m just building a monster right now. I’m doing this thing called The Beast with a Million Eyes,” which I hadn’t even heard of, I had no idea what it was, and he said, “I’m doing a little puppet thing for it.” And so he invited Kathy and me up to [his home in] Topanga [Canyon] to see what he was doing and, like that old, total cliché, the rest is history. The four of us just happened to click. They were pretty much recluses. They didn’t have a lot of friends and didn’t want a lot of friends. They were pretty much loners.

Paul always thought his monsters weren’t as good as they could have been. You’ve probably read about it. There was no budget, no time, and he always felt he could have done better—and probably could have, if he’d have had a bigger budget, time, a lab—you know, he didn’t have any lab and things like that. He didn’t even know what foam rubber was at the time. He was totally self-taught. That was the interesting thing about him. It was why his monsters were so unique and looked so cool; it was because he did them by the seat of his pants. There were no schools then like there are now. There’s hundreds of them now. He just went to the local place where you could buy foam rubber to stuff a couch, you know. He’d buy blocks of that—one-inch thick, two inches—whatever he needed—and just start that way. The only time he used a real negative mold, that I know of, was when he did It! The Terror [from Beyond Space; United Artists, 1958], and that was way down the line. He just built stuff up, he didn’t know any other way of doing it.

He did very few sketches that I saw. Usually he would sculpt it up in a miniature. He used to built model airplanes; the old kind that had the struts and all that kind of stuff; and he knew a lot about paint—what they used to called dope in those days—and he’d get that sheen [on his work]. He used a lot of that stuff—things that nobody would use on clay or rubber. The paint he used on his monster suits, for the most part—if he was doing the small detail work with his airbrush—was colored inks.

The [first] time we went up there, the puppet for The Beast with a Million Eyes was already done. He had that and that’s when he gave [a wax casting of it] to me.

Even by the most liberal of standards, and by no fault of Blaisdell’s, The Beast with a Million Eyes is difficult to sit through. Blaisdell’s monster follows the logic that a truly incorporeal being would need a conduit to the material universe in order to realize its plans of conquest. Thus, his marionette creature was meant to be a slave of the Beast, and not the Beast itself, and is briefly glimpsed in shackles. The marionette was ingeniously constructed and marvelously detailed. Blaisdell took to nicknaming most of his creations and this one he dubbed “Little Hercules.” The filming of this added footage was rushed, however, and in the end a leering eyeball and a diaphanous spiral were superimposed over the action, perhaps to camouflage the limited and hurried nature of this concluding scene, but in the end, obscuring the restrains and many of the other attributes that Blaisdell had so judiciously built into his highly imaginative creation. The artist was understandably disheartened, but it was only a matter of a few weeks before Corman called on him again, asking him to supply another monster for one of his films.

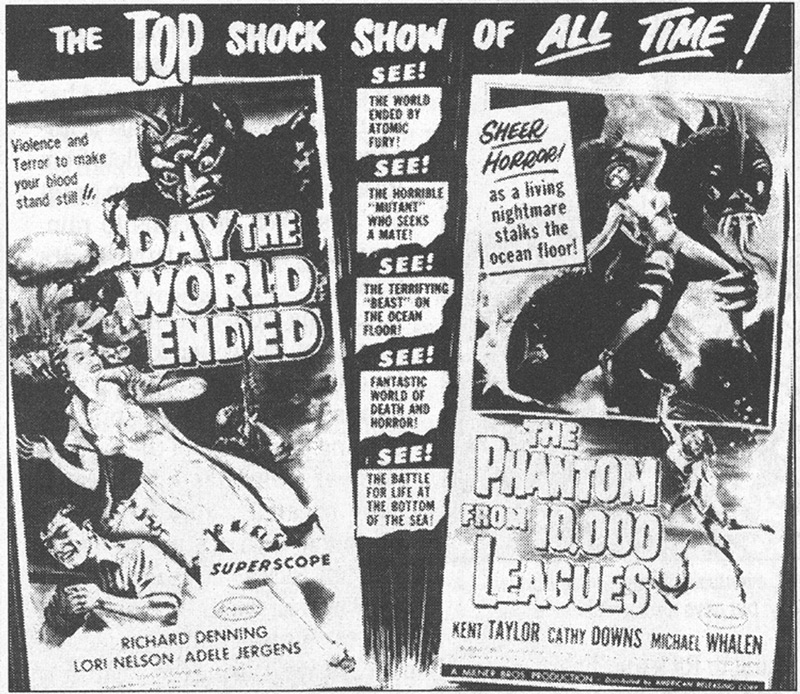

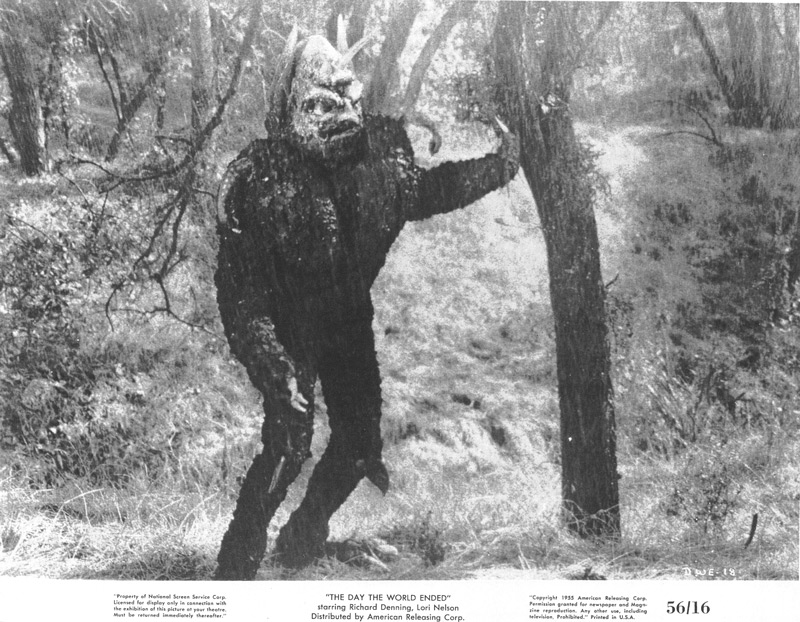

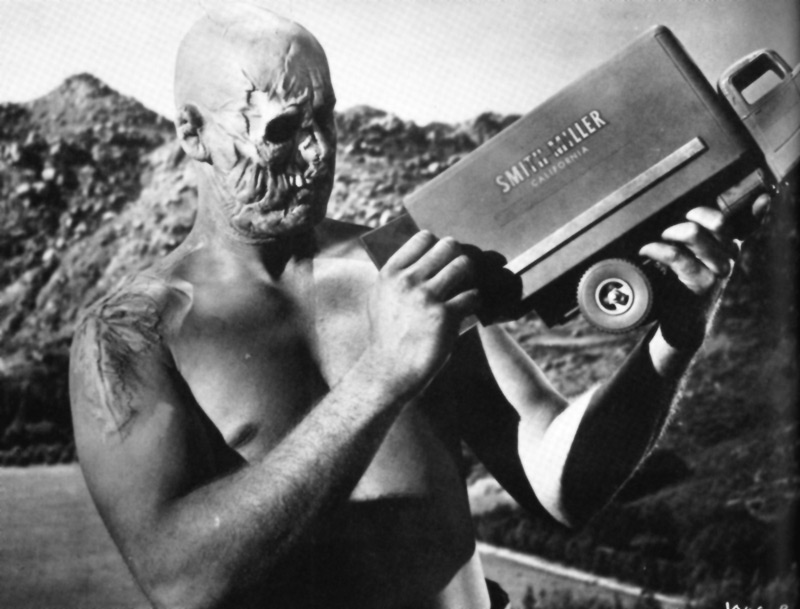

With the Cold War at its height by the mid-1950s, Roger Corman’s plans to film a grim vision of the post-apocalyptic future based on Lou Rusoff’s original story and screenplay, Day the world Ended (ARC, 1956), required the fabrication of a whole-body appliance to represent a ghastly atomic human mutant. It was Paul Blaisdell’s first monster suit for the movies and also his initial appearance before the cameras in the role of the aforementioned atomic mutation. The film also marked Corman’s directorial debut in the genre and was the top half of ARC’s first science fiction double feature, linked with another Lou Rusoff-scripted cheapie, The Phantom from 10,000 Leagues. Soon after, other studios such as Columbia and Universal followed suit with their own creature double-bills. Roger Corman, in his book How I Made a Hundred Movies in Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime (co-authored with Jim Jerome, Delta Books, 1991), explains: “[ARC and its successor, AIP] had been getting rather modest rentals for their previous films. With this double-bill experiment, exhibitors agreed to give them the same rental figures as they paid major studios. This pioneering strategy—two low budget films from the same genre on a double-bill—was designed, in large part, to lure teenagers and young adults to drive-ins. It became a standard AIP approach once it proved…profitable.”

Day the World Ended begins in the year 1970 with civilization destroyed by an atomic war. A fog of radioactive debris settles everywhere, and in the ensuing chaos, fearsome beasts lurk—mutated creatures born of the nuclear inferno. At the crest of a hill overlooking an incongruously peaceful valley, the mutants wait, fighting among themselves for tribal supremacy; establishing a new order for a New Stone Age. The persistent winds and the encompassing mountains, rich in lead-bearing ore, have protected the valley from the ravages of nuclear fallout. There, nestled on an upper slope of the hillside, is the Maddison home, where seven human survivors converge.

Captain Jim Maddison (Paul Birch), the owner of the house, has foreseen the war and has prepared for its aftermath. He has packed the house with provisions for three: his daughter Louise (Lori Nelson), himself and “Tommy,” a character we never see (at least not in human form) and whose relationship to the Maddisons is never made clear. For those not killed in the first few moments of the war, there will be a slow, ghastly transformation into something demonic. This is to be the fate of humanity unless, by some miracle, the air is suddenly cleansed. The remainder of the cast consists of Richard Denning as a geologist named Rick (in effect, the movie’s hero), Paul Dubov as Radek, a man hideously scarred by radiation and apparently near death, “Touch”—Mike—Connors as small-time hood Tony Lamont, Adele Jergens as Tony’s moll Ruby, and Raymond Hatton as a cantankerous old prospector named Pete who arrives with his trusty mule Diablo.

Tony takes an impious interest in the beautiful Louise upon first laying eyes on her. Captain Maddison, however, has other ideas. From the time of their first meeting, Maddison has taken a liking to Rick and has advocated that he and Louise pair off to begin the process of repopulating the Earth. With Maddison gravely ill from exposure to the radioactive fog while attempting to rescue the old prospector, Pete, the relationship between Louise and Rick begins to flourish. The sheltered and naive, Louise, in typical ’50s fashion, requires the strength and authority of a righteous male to give her a sense of security and balance.

While luring Louise outside where he plans to rape her at knifepoint, Tony is foiled in his attempt by Ruby. Louise runs back to the house and Tony and Ruby have an angry exchange, during which Tony stabs Ruby and throws her body off a cliff. Of the seven humans, now only four remain, with Jim Maddison barely clinging to life.

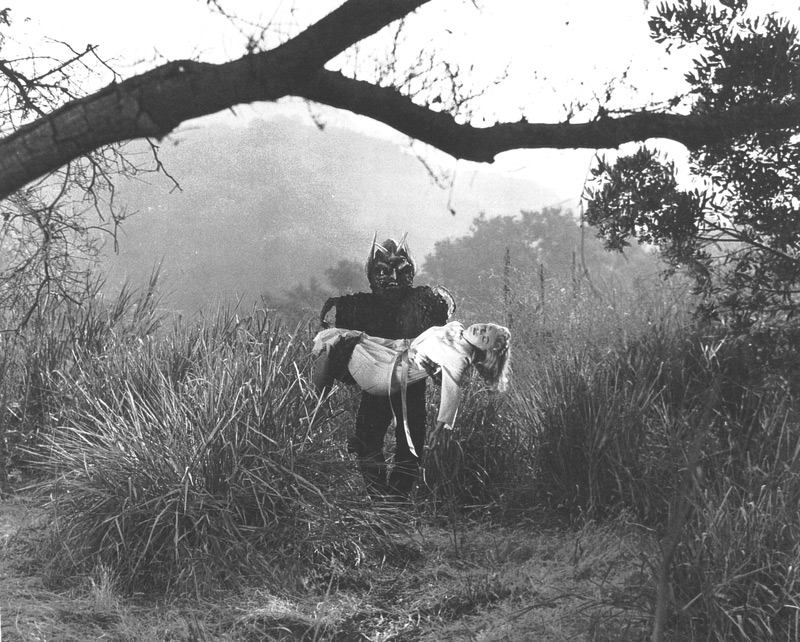

Later, a mutant (Paul Blaisdell) captures Louise while she takes a swim, but she manages to escape. That night the mutant makes its way past Louise’s bedroom window, calls to her telepathically and lures her out into the night where he kidnaps her. The suggestion is made, but never clarified, that the mutant might be Tommy and that Tommy might once have been Louise’s lover. Rick goes in pursuit, armed with a rifle taken from Maddison’s storeroom. The beast, however, is impervious to the hail of bullets from Rick’s rifle as it charges him. Just then it begins to rain, stopping the creature in its tracks. The rainwater mysteriously fells the mutant and after a time causes him to decompose. During the creature’s previous attempts to stalk Louise and Ruby while they bathed, the women instinctively sought refuge in the water where the beast seemed fearful to follow. It now becomes clear that the purity of the rainwater is lethal to the mutants, for they have adapted to survive in the toxic atmosphere of the post-atomic world.

At the house, Tony takes a sample of the rainwater for Captain Maddison to test. The water tests pure, suggesting an increasing likelihood of the group’s survival. Tony, however, readies himself by a window with a gun, intent on shooting Rick as he returns and taking the girl for himself. Tony takes aim as Rick and Louise approach after their ordeal with the mutant. Jim Maddison, lying gravely ill on the couch behind him, uses a pistol that he’s secreted under his pillow to shoot Tony to death before he can carry out his plan.

When the couple enters, Maddison tells them that he’s received a message by radio. There are other survivors out there and with them a greater chance for humanity to start anew. “There’s a future out there for you,” he says. “You’ve got to go out and find it.” Having said that, Maddison closes his eyes and promptly expires. As Rick and Louise set out into the wilderness with their backpacks on and hope in their hearts, the film concludes with the words, “The Beginning.”

Filmed in SuperScope, a widescreen process similar to CinemaScope, this modest black and white movie is far more enjoyable than much of the low budget fare of its day. Among its more obvious attributes is a crisp, uncluttered look to its cinematography, despite its considerably restricted view of the post-atomic world. But it is a memorable bit of atomic pop culture and it provides an engaging mirror of the views Americans once held about World War III in those grim days of the Cold War; especially with regard to the survivability of a nuclear exchange. Although we are told that Maddison has set up his sanctuary with its own power generator and supplies, much of the action goes on as though the world has not been greatly altered by the terrible atomic catastrophe. This calamitous event is presented as little more than a bump in the road—an inconvenience of several weeks as the winds purify the air of undesirable contaminants so that life can eventually return to normal.

The few scenes of devastation are provided by documentary footage from World War II, while standing in for Maddison’s valley is Bronson Canyon in the Hollywood Hills near Griffith Park. The pond where several important scenes take place, including the climactic confrontation between Rick and the mutant, is actually located behind the Sportsman’s Lodge, a restaurant on Ventura Boulevard. Corman’s film crew was allowed to work behind the restaurant during the day, provided that shooting was completed and the equipment gone by the start of dinnertime seating in the early evening.

The real star of the picture is, of course, Paul Blaisdell’s monster, a fearsome concoction of foam rubber and paint built over a pair of long johns. As was usual, Blaisdell nicknamed this new creation “Marty the Mutant.” Bob Burns explains the fabrication of Marty’s costume:

Paul took pieces of foam rubber and he literally just tore them into little, teeny bits. It took him and Jackie probably a week just to tear the stuff. He tore them just like you would tear up bread for a Thanksgiving stuffing; so that no one piece was exactly the same as another. Then he glued them onto long johns with contact bond cement… He and Jackie glued all those pieces on. It took forever.

The headpiece was pretty interesting. That was built up over an army helmet liner and the top part of the head, the sort of pointed shape up at the top, was actually made out of plaster over a wire framework that he’d built up over the helmet. In the few close-up stills—of course, there aren’t many close-ups of the suit—you can actually see some cracks in the plaster. The ears he made out of a form of resin—probably Fiberglas at that time—I don’t know if they even had resin in the ’50s. The head was built up so he had to look out through the mouth, so he wore a pair of sunglasses behind it. And the teeth he sculpted up himself and I think those were out of clay. The horn things were flexible; it was a kind of early vinyl that he used. He sculpted up Marty’s face out of this resin-like material. There wasn’t much rubber on the head at all…He used to get his supplies from a place called Frye Plastics—it’s not even in business anymore. He got everything in Frye Plastics. They had the resin material, they had the Fiberglas there, they had the little plastic spheres that he’d use for eyeballs, and all that stuff.

It was the first actual monster suit Paul ever did. He wore the suit because at the time it was before the unions got in and they didn’t yet care about such things. They didn’t have anyone else in mind to play the mutant and Paul didn’t know what else to do, so he just built the suit for himself and that’s how he did most of those in the early days.

He was about five eight and a half; kind of a small guy. With Marty now, you really couldn’t tell. He’s never in scenes with anyone else close up except the girl [Lori Nelson] and she was not very tall. But you never saw him that close in proximity with the other actors. Now with The She-Creature, later on, he made a pair of built up shoes. But Marty was just his size. The chest was built up with foam rubber—a big foam rubber pad that snapped up the back. Today they’d use Velcro. He built it out of solid foam rubber and he glued these tiny little blobs of torn foam all over it. It was like a two-piece suit, actually. He made the bottom part like a pair of pants. And then the whole trunk part—top part, the upper torso—fit down over it. And being all dark—it was a very dark, chocolate-brown color—it just fit, and it didn’t appear to separate very much. And then the head just fit over that and it had snaps, too. It was like a hood, almost. The eyes were, again, from the Frye Plastics Company. He got these big spheres that he found, and he had a way of doing the eyes—he did this on [Little Hercules from The Beat with a Million Eyes] originally—the back part of the eyes would be like a copper color—it would almost reflect like a cat’s eye. It was kind’ a neat—and then he’d paint the pupils on these spheres. He sculpted the baby arm things [at the shoulders] in clay and used the technique of painting the latex over them, then slit them underneath and took them off. He stuffed them with cotton, I think—or anything he could find.

He also did the real crude drawings of the monkey-like things [that appeared in the film]. He made them very crude on purpose. It’s supposed to be that this guy [Captain Maddison] sketched them [from his observations after the Matsuo Nuclear Bomb Tests].

But I thought that Marty was a totally innovative suit. It was a cool looking thing. Body English—this is what monster suits are all about…I just think he was one of those guys—he was given a challenge and he would just figure out how to do it. The body English in Marty was great, because the face was totally immobile, nothing moved—the mouth didn’t move, the eyes didn’t move, or anything—but that thing had a lot of character to it…the way he moved the monster—that was [it].

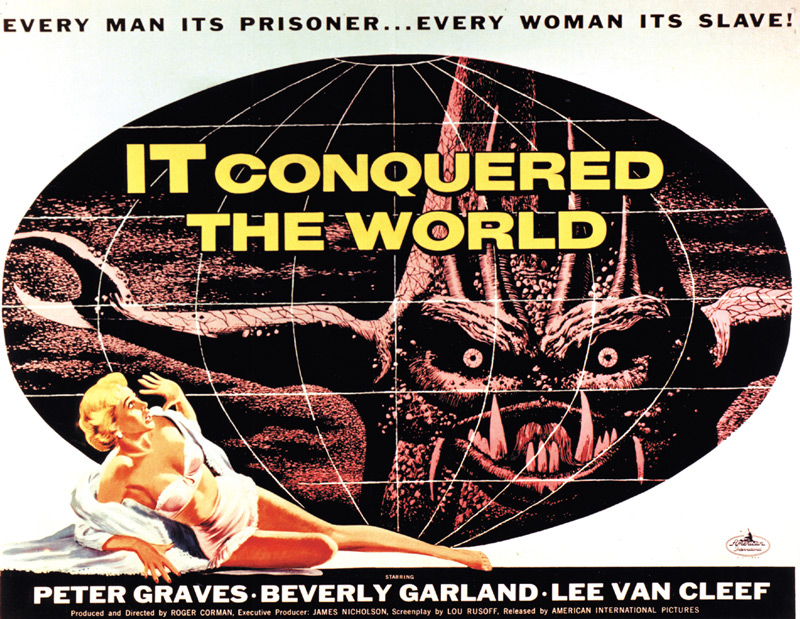

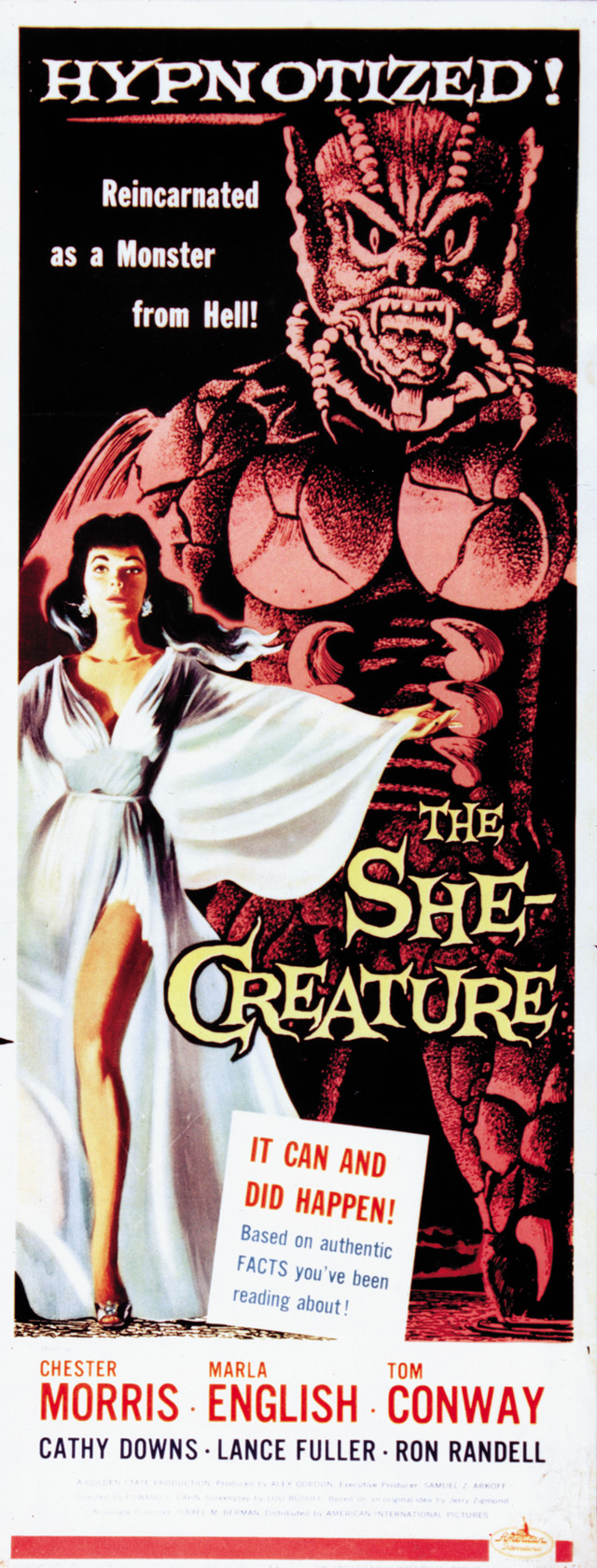

Blaisdell’s next project, It Conquered the World, was also for Roger Corman, and for Nicholson and Arkoff’s newly renamed company, American International Pictures. This film dealt with the theme of alien invasion and would be the first motion picture to introduce the concept of biomechanical lifeforms. It, like Day the World Ended, was teamed for co-release with another AIP science fiction picture, The She-Creature. The title character for the co-feature would also be a creature of Blaisdell’s making, and is perhaps one of the most recognizable and imaginative monster suits of the 1950s.

In It Conquered the World, which is one of Roger Corman’s best science fiction films of the period, scientific wunderkind Tom Anderson (Lee van Cleef) is in secret radio communication with a creature from Venus. The being is one of only nine surviving members of its species, who have evolved too soon in Venus’s turbulent atmospheric development for them to subsist. With Anderson’s help the creature conspires to hijack a government satellite and to use the device to journey to Earth. In exchange for his cooperation, the alien promises Anderson that life on Earth will change for the better. The eccentric Anderson’s greatest fear is that, without the creature’s intervention, humanity will ultimately destroy itself.

Anderson’s best friend is Dr. Paul Nelson (Peter Graves), a physicist and the scientific head of the government satellite project. Nelson is called away from an evening dinner party at Anderson’s home when a recently launched satellite disappears from orbit. By the time he arrives at the launch complex the device has inexplicably returned, prompting the scientists to bring the satellite back to Earth to determine the cause of its erratic behavior. As the satellite descends it veers wildly off course and crashes into the mountains in the proximity of Elephant Hot Springs—a network of caverns, the interior conditions of which approximate the fierce, sulfurous atmosphere of Venus.

Once on Earth the creature releases eight bat-like control devices from its body—apparently, biomechanical lifeforms—that seek out specific individuals, implant tiny control antennae at the base of their skulls, then die like mosquitoes after attacking their victims. Anderson has targeted four key members of the community as initial control subjects: General Pattick (Russ Bender), the military head of the satellite complex, Mayor Townsend, the mayor of Beechwood, Chief of Police Shallert (Taggart Casey) and Paul Nelson. The four remaining devices are intended for their spouses. The creature’s next move is to neutralize all the Earth’s power, except to those under its direct control.

Anderson’s wife, Claire (Beverly Garland), argues constantly with her husband about the alien’s motives, questioning the creature’s need to deprive people of their free will. When Paul Nelson is finally convinced that Anderson’s claims of the alien presence are indeed true and not a delusion, he, too, attempts to appeal to Anderson’s better nature to stop aiding the being in its plans.

In a truly chilling scene, Joan Nelson (Sally Fraser), Paul’s wife, lovingly launches one of the bat creatures at Paul in the hope that he will be taken over. Blaisdell called these bat creatures “Flying Fingers.” Failing in her attempt, Joan is shot to death by Paul. Paul, now deeply distraught over the necessity of having to shoot his wife, arrives at Anderson’s home with a gun, intent on killing him. Tom Anderson, under instructions from the Venusian, also plans to kill Paul, but soon discovers that his wife Claire has taken his rifle and gone to Elephant Hot Springs to confront the creature. On his radio, Tom hears Claire’s futile cries for help as the alien attacks and kills her.

In the meantime, a soldier, Private Manuel Ortiz (Jonathan Haze), has separated from his detail and gone off to forage for food. He hears Claire’s screams coming from the caves and looks within to see her being assaulted by the alien. He summons the rest of his detail and they head off to the caverns to do battle with the invader. Tom, on hearing what’s happened to Claire over the radio, comes to his senses and he, too, heads out to Elephant Hot springs. Paul, in the meantime, drives to the satellite complex to kill General Pattick and two of his fellow scientists who have been taken over by the alien (we learn that the mayor and his wife have been killed during the evacuation of the town, leaving the two remaining control devices free to be used on Paul’s colleagues).

At the caverns the soldiers draw the creature out into the open. Tom Anderson advances calling the soldiers off, then burns out one of the creature’s eyes with a blowtorch as the monster strangles him. After a short struggle, the two topple over dead. Soon after, Paul arrives. Sgt. Neil (Dick Miller) says to him in bewilderment, “He acted like he knew it.” “He did.” Paul responds, “He and no one else.” As he looks down at Tom’s lifeless body, he continues, “He learned almost too late that Man is a feeling creature, and because of it, the greatest in the universe. He learned too late for himself that men have to find their own way and make their own mistakes. There can’t be any gift of perfection from outside ourselves. When men seek such perfection they find only death—fire—loss—disillusionment—the end of everything that has gone forward. Men have always sought an end to toil and misery. It can’t be given, it has to be achieved. There is hope, but it has to come from inside—from Man himself.”

The script, screen-credited to Lou Rusoff, but apparently written by Charles B. Griffith (who also played the small part of Pete Shelton, one of the colleagues that Paul Nelson shoots during the film’s finale) is full of imaginative and well-conceived touches. Many of these ideas come directly from the fertile mind of Paul Blaisdell, a seasoned science fiction reader, who spent considerable time brainstorming with Rusoff prior to the writing of the script. Almost certainly, the idea of the creature’s biomechanical control devices comes from Blaisdell, who sought a means for the largely immobile alien to carry out its plans of earthly conquest. Although not an entirely new idea to SF literature (A. E. van Vogt used bio-mechanical constructs in his stories as early as the 1940s, and was probably not the first to do so), it was completely unknown to film in 1955—and, remarkably, remained largely unused thereafter in the cinema side of the genre until the late 1970s.

One thing, alone, sabotaged the effort to make this a quality picture: the simple lack of budget. During the climactic confrontation at Elephant Hot Springs (actually the caves at Bronson Canyon in the Hollywood Hills, with fog machines and smoke pots in place to suggest a sulfurous environment), the sequence in the caves was photographed entirely by natural light. Portable electric lights had been provided for the day’s shooting, but were left behind. As the day wore on and the caves grew too dark to film in, Corman insisted that the creature be drawn out into the open. The time involved in retrieving the lights and setting them up would have necessitated adding another day to the shooting schedule. To add insult to injury, Corman also insisted that both Lee van Cleef and the alien fall over dead—a feat that the odd, tepee-shaped prop could not easily achieve. It is there, in the revealing illumination of broad daylight that Blaisdell’s creation appears most outlandish. Audiences broke into laughter at this critically dramatic point in the movie, and Blaisdell walked out of the L.A. premiere screening convinced that he would forever be the target of ridicule. Critics certainly noted the ludicrous appearance of Blaisdell’s creation, but filmgoers, though they found it momentarily amusing, hardly seemed to notice. The scene was further immortalized in a spoken-word prologue to the song Cheap Thrills by rock star Frank Zappa (included in the album, Cruising with Ruben and the Jets, 1968).

Two incidents of note occurred during filming and tellingly illustrate the highly rushed and restrictive circumstances under which It Conquered the World was filmed. The first involved a potentially fatal accident in a scene in which actor Jonathan Haze as Private Ortiz charges the Venusian in the cave with a bayoneted rife. Intuitively sensing that there might be danger in the day’s activities, Jackie Blaisdell insisting that her husband wear an army helmet while operating the creature (whom the Blaisdells nicknamed “Beulah”) from the costume’s cramped interior. When he emerged after the scene with Haze, the helmet had a sizable ding from the bayonet penetrating the alien’s flimsy one-inch thick foam rubber hide.

The result of the second incident is detectible on screen. Blaisdell had devised a system to operate the creature’s arms, allowing it to snap its claws open and shut. The system involved the cable linkage from a bicycle breaking system and an air pump. In the haste of the day’s filming, Blaisdell neglected to tie the creature’s long arms upright, which had been his routine to keep the delicate interior operating mechanism from harm. Randy Palmer, Blaisdell’s biographer, explains in Paul Blaisdell: Monster Maker (McFarland, 1997) that, “Unfortunately, the pincer cables snapped in two before they ever got a celluloid workout…Someone on the crew pushed a heavy-duty film cart across Beulah’s limbs, snapping the delicate cables inside. With Corman directing there was no time for repairs…so Beulah was pressed into service with two broken arms. Sure enough the rubber pincers flopped lazily back and forth on screen, making the entire project look exceptionally cheap…”

In the adept hands of director Edward L. Cahn (1899-1963), the filming of The She-Creature had been less troublesome for Paul Blaisdell than had been its co-feature, It Conquered the World. Unlike Corman, the pragmatic Eddie Cahn, known to move with efficiency and dispatch through the daily set-ups, tended to stick more closely to his scripts.

This time the title for The She-Creature came not from James Nicholson, but rather from one of AIP’s sub-distributors, Newton Jacobs, who later became the president of Crown International Pictures. The story, by Jerry Zigmond, was based on the headline-grabbing tale of Bridey Murphy, a purportedly 18th century Irish woman who had been reincarnated as a mid-20th century Pueblo, Colorado housewife named Virginia Tighe. The event had been the subject of a best-selling book, The Search for Bridey Murphy (Doubleday, 1956), written by businessman and amateur hypnotist, Morey Bernstein, and had, for a brief time, captured the imagination of the public. To protect her anonymity, Ms. Tighe was referred to in the book as Ruth Simmons. Tighe recounted her story of a past life while under time regression hypnosis, a therapeutic technique of modern psychology and one often employed in the treatment of past-event emotional disorders. In Zigmond’s screen story, however, a beautiful woman would be regressed a million years or more to a point at which she projects the specter of a hideous primeval aquatic lifeform. Once the bare outline of the story was set, Blaisdell was called in to create the title creature and scripting chores were again handed off to Lou Rusoff.

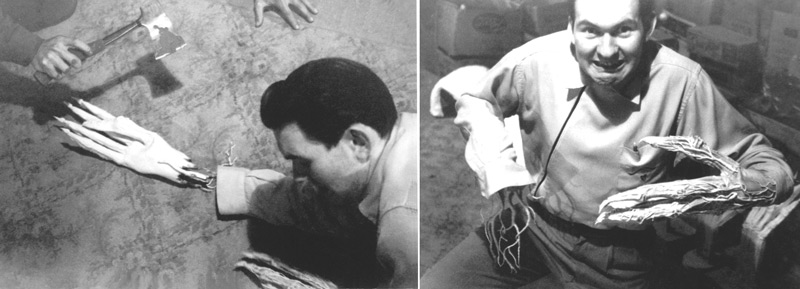

Blaisdell’s approach to this new endeavor was not unlike the one he’d used for Marty in Day the World Ended, utilizing a pair of common long johns as a foundation. Bob Burns recounts some details of the process:

For The She-Creature Paul created a totally unique monster for its time, and it was his favorite. It really didn’t look like anything else at all. As usual, he had to take all the shortcuts with that, too. The hands with the big hooks coming out were all carved out of white pine and they were built over welder’s gloves. You can see a thumb—the thumb is in the sculpture. He covered it with rubber, but there is a thumb.

He did a sort of jigsaw puzzle design out of foam rubber [to form the scales] and glued them onto the pair of long johns. Jackie was very instrumental in the work on these things, too. They were a team; they were a complete, absolute team. She was very clever in her own right…They would lay out the foam rubber on the floor, draw this sort of jigsaw puzzle design and then they would cut it out and fit it all together on the suit. When you consider how many people it took to make the [Gill Man in] Creature from the Black Lagoon, and here Paul and Jackie did this all themselves. I think it took between four and six weeks for them to complete. That was the longest he ever got to work on a creature; that was the She-Creature—the luxury he had of a little time. But it was just so amazing!

He sculpted up the face over what he called a “blank” of himself. Jackie made a whole plaster cast of his head—this was before this stuff was being done and they had to figure out how to do it. So, he had this plaster blank of himself and he would paint a face out of latex on top of that and that’s what he used to sculpt the She-Creature’s face on…Again, he was cutting up the little foam rubber pieces, gluing them on and then painting them over with latex. And then it was an ingenious idea to put the little rhinestones in the eyes. The eyes would glisten if the lights hit them right. For the She-Creature, those were [novelty] vampire teeth—those plastic vampire teeth that glow in the dark. He took two pairs and put them together. He’d use stuff that he’d find. The feet were made over a pair of swim fins.

In The She-Creature, Dr. Carlo Lombardi (Chester Morris) is an ascetic, small-time sideshow hypnotist who has inordinate power over his subject, a beautiful but mysterious former carnival groupie named Andrea (Marla English). By putting the girl in a trance and regressing her, Lombardi is able to reawaken Andrea’s primeval self—a murderous prehistoric sea creature. Through Andrea, the hypnotist summons the creature and sends it off to commit a series of gruesome killings. Lombardi predicts the murders during his performances and a hardnosed businessman named Timothy Chappel (Tom Conway), exploits the attendant publicity, transforming Lombardi into a virtual overnight celebrity.

Dr. Ted Erickson (Lance Fuller), a professor of psychic research, questions Lombardi’s motives, and is certain that he is somehow linked to the gristly murders. In the process of observing Lombardi, Ted falls for the beautiful Andrea. With Ted’s help, the girl begins to resist Lombardi’s hold over her, and she, likewise, finds herself attracted to the gentle and well-meaning professor. Obsessed with Andrea and jealous of her growing fondness for the professor, Lombardi brings forth the She-Creature to murder Erickson, but because the creature is ultimately a manifestation of the modern-day Andrea, it turns instead on Lombardi and kills him. As the monster lumbers off to sea never to return, Lombardi tells Andrea with his dying breath that she could not bring even her prehistoric self to kill Ted, the man she truly loves.

With its theme of regression hypnosis and its frequent references to the occult, The She-Creature sounds like a traditional horror movie, but it looks and feels very much like science fiction. The science of the story assumes the reality of reincarnation and the existence of a spirit world, but beyond that, little effort is made to provide the exposition that would place this motion picture squarely in one camp or the other—nor does it need to. Clearly its premise is meant solely to support the existence of its title character, for this is unabashedly a monster movie with few allusions to a higher purpose. As such, although limited in ambition, it is refreshing in its brevity and its lack of pretense. Again, Blaisdell’s creature, affectionately dubbed “Cuddles,” is, by far, the main attraction of the film, and is today well regarded in the pantheon of 1950’s science fiction movie monsters.

Blaisdell’s next project was also inspired by Bridey Murphy and the subject of reincarnation, and was developed by Roger Corman under the working title of The Trance of Diana Love. Released by AIP in late 1956 as The Undead, it contains no science to speak of and is more on the order of a supernatural fantasy. For it, Blaisdell revamped two of the Flying Fingers from It Conquered the World to double as bats and he also appears briefly in the film as a corpse. In that same year he played a small part as an accident victim in AIP’s teen-targeted saga of slick chicks and souped-up cars in Hot Rod Girl.

The movie Voodoo Woman occupied Paul Blaisdell through the winter of 1956-’57. It used many of the same cast members as The She-Creature, as well as its producer, Alex Gordon, and its director, Eddie Cahn. Despite its title, and its marginal mixing of science and magic, it is clearly an SF movie of the mad scientist variety. Because of Voodoo Woman‘s marginal financing—reputed to have been under sixty thousand dollars—and an abundance of commitments elsewhere (Blaisdell worked on an astonishing eight films that were released in 1957 alone), after doing some preliminary sketches, Blaisdell declined to finish the designs for the title monster when further budget cuts were made. He did agree to rework the She-Creature suit, however, provided that AIP secured the services of someone else to design a new headpiece for the costume. To that end, Harry Thomas, a make up artist who’d been active in the low budget science fiction film genre at the time, was called in. Bob Burns recalls the incident:

What Harry Thomas did was to go down to the local magic shop and buy one of those Topstone skull masks. He put a white wig on it, and that was it. Then he took it to the studio. Paul was busy with something else—I can’t remember what—but he didn’t really want to do it. Then, of course, they had to come to him and say, “We can’t use this; can you help us?” Now, they’d already decided that they’d reuse the She-Creature costume and had Paul redo the suit, which he’d agreed to do, but to have somebody else do the head. When they brought Thomas’s mask to him, Paul called me and said, “You’ve got to come over and see this.” You know how they always had those eyeholes punched off center [in those cheap commercial masks]? Paul finally put some eyes in it and put in some teeth—little fangs and stuff—just to try to help, and then he built it up with some gum rubber—the cheekbones and stuff like that, and he put the Blaisdell scowl in it, of course. He did the best he could and he rebuilt the thing in two days. But Paul was never happy with that, because it was never really his.

Roger Corman’s relationship with AIP had not been an exclusive one and in 1957 he produced and directed two films for Allied Artists for which he approached Blaisdell, seeking his participation. The first of these, Attack of the Crab Monsters, had such a small budget that Blaisdell seriously questioned if anyone would be able to devise a credible giant crab to match the rigors of its script, and so he declined it. It was possible, given a little forethought, that only one giant crab would be needed—and in the end, only one was actually built—but even so, Blaisdell felt the budget was simply inadequate to create a realistic-looking monster. The movie turned out to be a remarkably good one, thanks to Charles B. Griffith’s intelligent and highly imaginative screenplay and Corman’s capable direction, but Blaisdell’s reservations proved correct, and despite the film’s many entertaining qualities, the radiation-enlarged crabs—probably the work of property master, Karl Brainard—look genuinely preposterous.

The second of Corman’s film offers, Not of This Earth, was also a low budget affair, but required far less effort than the construction of a full-scale giant monster, and so Blaisdell agreed to take it on. Its plot centers on the theme of modern day vampirism, bringing to Earth a member of a humanoid race from the far off world of Davanna. The Davannans have been at nuclear war with each other for generations and suffer from a radiation-induced blood anemia. The mysterious Mr. Johnson (Paul Birch) has been sent here on a mission to find a new blood supply to save the people of his dying planet. If successful, the Earth would then be targeted for invasion. From this basic premise, Charles B. Griffith and Mark Hanna created a clever and original script that introduced the theme of matter transmission to the movie going public—a concept that had been a fixture of SF literature for several decades, but that was entirely new to motion picture audiences in 1957. A year later the idea would be put to effective use in Kurt Neumann’s The Fly (20th Century-Fox, 1958). The script also describes a protoplasmic robotic assassin that appears outwardly to be a dog. This murderous entity was later changed for reasons of practicality into a novel, umbrella-like creature devised by Blaisdell along the lines of the Flying Fingers. Operated by the same kind of fish pole device, the umbrella-shaped monster envelopes the head of a character named Dr. Frederick Rochelle (William Roerick) and apparently crushes it to a bloody pulp. The effect was startlingly graphic for its day. Not of This Earth went into national release on March 3, 1957 as the lower half of a double bill with Roger Corman’s Attack of the Crab Monsters. It has since been remade twice—once featuring former pornographic film star, Traci Lords (Concorde, 1988).

The casting of American actors in foreign films was long understood to be an effective way for foreign-made movies to gain access to the lucrative U.S. markets. AIP, in its constant quest to reduce production costs, buck the unions, and minimize financial risk, decided to exploit this idea and started ‘loaning out’ actors and screenwriters to overseas production companies as barter. Combined with a modest capital investment, the studio would, in so doing, acquire partial ownership in the resultant films. In 1957 AIP embarked on the first of several Anglo-American productions, a modest supernatural horror tale based on a script by Lou Rusoff entitled, Cat Girl. The story dealt with a lovely, but deeply disturbed woman named Leonora Brandt (played by British actress Barbara Shelley), who is a were-creature, capable of transforming herself into a leopard. In the hands of its director, Albert Shaughnessy, however, Rusoff’s tale of the supernatural became instead a psychological thriller in which the ability to transform into an animal is purely a matter of the protagonist’s troubled state of mind. RKO’s The Cat People (1942), a classic of the genre, handled the theme in a similar manner, leaving the actuality of the character’s transformation open to interpretation. Finding Shaughnessy’s film unacceptable as it was, however, James Nicholson contacted Paul Blaisdell on a Friday and requested that he produce a cat creature for a brief insert shot to be added to the film’s conclusion. With a deadline of only two days, Blaisdell created a cathead and paws and donned a pair of pajamas to enact the cat creature role for inserts shot at the studio on the following Monday morning. Taken in haste, this additional footage was photographed out of focus but was edited into the film anyway.

Cat Girl occupied the lower half of a double bill with Bert I. Gordon’s The Amazing Colossal Man (AIP, 1957), a film for which Blaisdell created props of various sizes to augment the illusion of a man (Glenn Langan as Col. Glenn Manning) growing progressively into a giant after being accidentally exposed to the world’s first plutonium bomb blast. Blaisdell’s props for the film also appeared in Colossal Man‘s sequel, War of the Colossal Beast (AIP, 1958).

Paul Blaisdell’s reputation for working quickly and cheaply spread throughout the low budget film community and before long he was entertaining offers from a variety of producers outside of his usual sphere at AIP. Not all of these ventures proved fruitful, however. One such producer, Al Zimbalist, approached him regarding a project entitled Monster from Green Hell (DCA, 1957), in which insect specimens inside an experimental rocket are exposed to radiation and are caused to mutate to giant proportions. For that production Blaisdell created a series of pen and ink drawings and was prepared to negotiate with Zimbalist for construction of a full-size monster for the film, but never heard back from Zimbalist despite repeated inquiries at the producer’s office. The title monster—or, actually, monsters, there was a veritable swarm of them—turned out to be giant wasps and were finally realized through the process of stop motion animation, executed by special effects artist Gene Warren. To save money, Warren built the wasp models over wire frames, rather than using traditional steel ball-and-socket armatures.

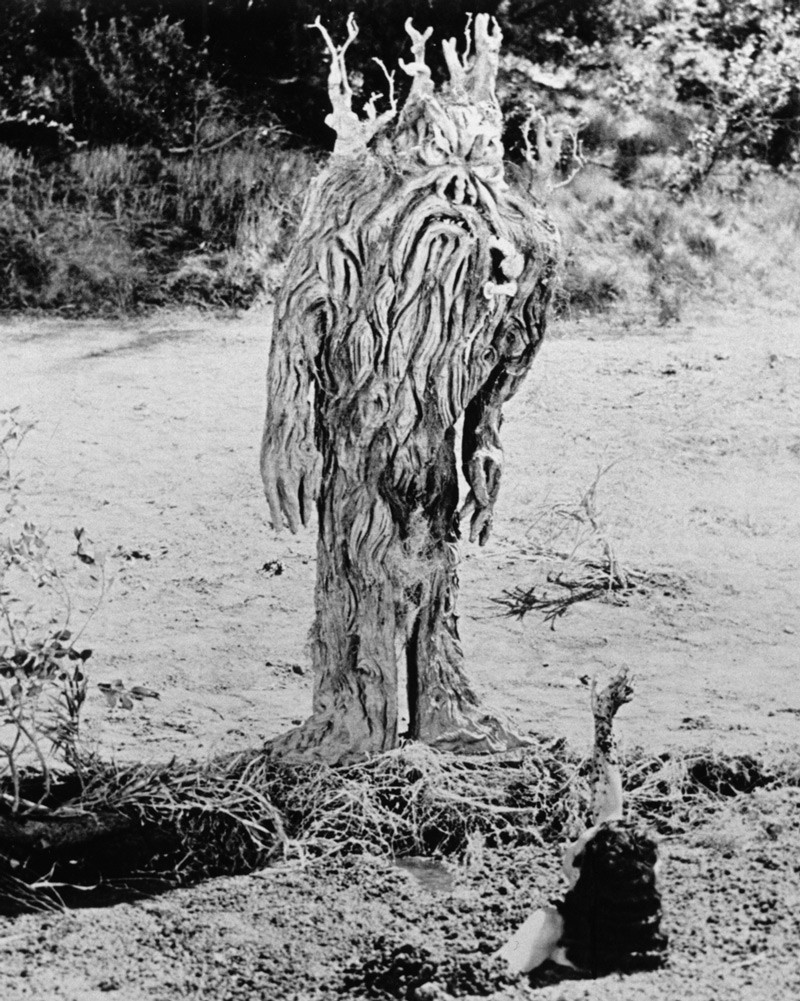

Another project, produced by brothers Jack and Dan Milner for Allied Artists, involved the occult but made a small concession to science fiction in that an ambulatory tree, inhabited by the spirit of a tribal warrior, is situated in a field which has been exposed to radioactive materials. Entitled From Hell It Came (1957), the film is best remembered today for having presented one of the most ludicrous looking SF movie monsters of the 1950s. For the Milners Blaisdell prepared a number of color sketches, but final construction of the tree monster costume was done at the Don Post Studios in Hollywood without Blaisdell’s knowledge or participation. Bob Burns commented recently on both of these incidents:

I don’t know what happened to the sketches for Monster from Green Hell. Al Zimbalist was the producer on that and Paul never got paid and the same thing is true of the Milner brothers on the Tabanga [in From Hell It Came]. Fabrication for that was done by Don Post Studios, but it was clearly Paul’s design. Paul never got paid and never got his sketches back, either. He didn’t even know until the film was done that any of his stuff was going to be copied—which it definitely was. The first design he did was really pretty neat. It was more like a real tree. Only, even the arms would have [had to have been manipulated] like those of a marionette. They would have been like tree branches and nobody on Earth would have arms that thin. He abandoned that right away, because it had to have arms. But if you look at the sketches and you look at what they did, it’s very obvious [that the Tabanga was based on Paul’s designs]. He had a lot of bad experiences that way, too—being ripped off.

Corman was always cost conscious, but one thing about Roger, he would always tell you going in, “Look, I don’t have any money. Do it as cheaply as you can.” And I don’t think Paul ever had—outside of that one real argument he had about [showing] Beulah—I don’t think he ever had anything bad to say about Roger. I think he actually enjoyed working for Roger, otherwise. [Roger Corman’s] true reputation is not as tainted as you might think. A lot of people may have said some rather bad things about him, but Paul always got along with him. And Paul, even in [Randy Palmer’s book, Paul Blaisdell: Monster Maker] said some really nice things about him. Paul never really attacked anybody. He wasn’t that kind of guy.

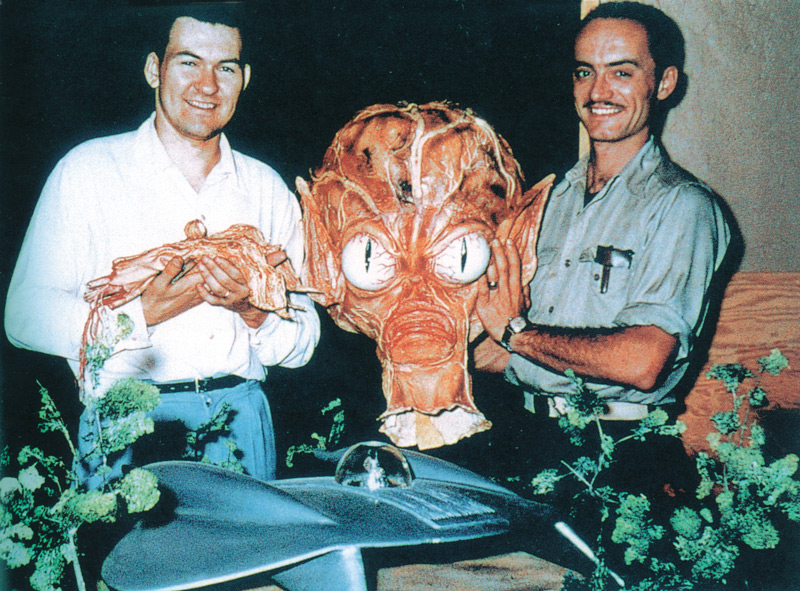

Invasion of the Saucer Men (AIP, 1957) is a lurid little film to which few critics have been kind. It is a rare science fiction comedy, but not much of it is very funny. In addition, it is quite spare in its production values, and it has no real stars of which to speak. It does, however, feature Paul Blaisdell’s outrageous, cabbage-headed aliens and his sleek swept-wing flying saucer. This film, perhaps more than any other with which his name is associated, established Paul Blaisdell once and for all as a consummate master of low budget movie monsters. And there is no diehard SF movie fan that I know of who, having seen it, hasn’t come to love it over time.

The film seems to have come into existence initially for the purpose of filling out the lower half of a twin bill with the better-known, youth-targeted science fiction/horror movie, I Was a Teenage Werewolf, yet it is as well remembered today as virtually any SF film of the 1950s. Part of the reason this is so may lie in the fact that it is one of the few cinematic attempts to show the proverbial “Little Green Men” of science fiction literature—although the Little Green Men represented here are not green at all (of course, in a black and white movie that would hardly seem to matter). Based on “The Cosmic Frame,” a little-known short story by Paul W. Fairman (1916-1977), its script, by Robert Gurney, Jr. and Al Martin, once went by the intriguing title of Spaceman Saturday Night. The idea to make the movie came directly from James Nicholson who believed that no previous film had attempted to portray such a vivid and well-recognized genre icon. He was wrong, of course, for Edgar Ulmer’s The Man from Planet X (United Artists, 1951) had done precisely that six years earlier, and so had a handful of other films (such as Hodkinson’s 1923 3-D film Radio-Mania) going back to the silent era.

A flying saucer lands in Pelham Woods, a remote site outside the sleepy hamlet of Hicksburg. There’s a hangout in the woods known to the local cops, a cantankerous farmer named Old Man Larkin (Raymond Hatton), on whose property the woods are situated, and a gang of teenagers, who’ve transformed the area adjacent to a cow pasture into a lovers’ lane. Diminutive extraterrestrials invade the lovers’ lane, inebriate Larkin’s prize bull and contribute to the death of con man Joe Gruen (Frank Gorshin) by stabbing him with their alcohol-filled fingertips. Gruen had already been drinking heavily by the time of his alien encounter and the additional alcohol pushes him over the edge.

The film stars Steve Terrell as Johnny Carter and Gloria Castillo as Joan Hayden; love-struck teenagers bent on eloping, who inadvertently run down one of the aliens with their car. As the teens go for help, the extraterrestrials substitute the body of their fallen fellow with that of Joe Gruen and pound dents into the fender of the kids’ vehicle in order to frame them (hence the title of the original story); thus undermining the teenagers’ claims and diverting attention away from the aliens’ presence here on Earth.

Lyn Osborn plays Joe Gruen’s partner Art Burns, and he is also the story’s wisecracking narrator. Osborn, known to science fiction fans for his portrayal of Cadet Happy on TV’s Space Patrol (ABC, 1951), passed away shortly after the film’s release. In the end, no adult will believe the teenagers’ claims of alien invaders and so the youngsters have to take matters into their own hands. When Burns attempts to photograph a reanimated, severed alien hand that tries to attack Joan, Johnny and himself, the groping member disappears in a puff of smoke, revealing the aliens’ vulnerability to intense light. Thus, with headlights beaming, the rowdy teens surround the creatures with their cars and finally put an end to their plans of conquest.

Bob Burns worked closely with Paul Blaisdell during this period and assisted him on the set of Invasion of the Saucer Men. Burns offers a fascinating first-hand account of the making of the film:

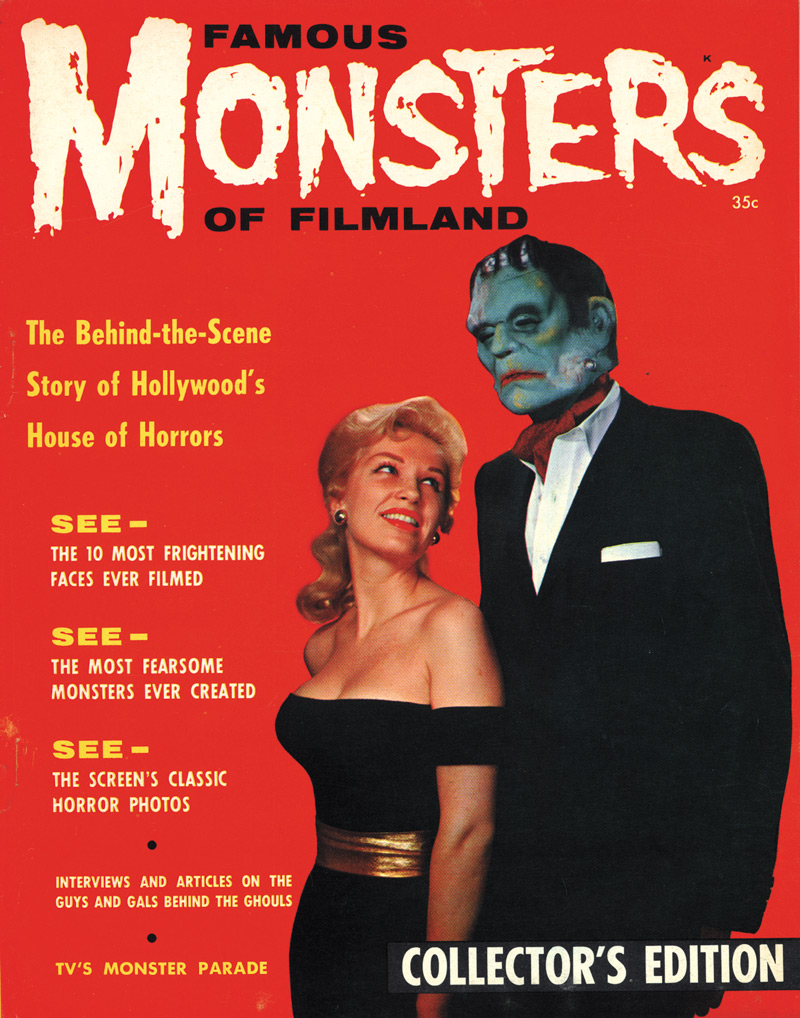

If Paul did some sketches of the Saucer Men, I never saw them. He might have done some preliminary sketches that maybe he showed to Jim Nicholson, or something, but I never saw them if he did. The one that was used in [the magazine] Famous Monsters [of Filmland, vol. 1, issue 1, 1958] was a [drawing] he did specially for that.

He did a “positive” sculpt and didn’t work from molds on them. He made a big brain pattern out of plaster over wire and for the face itself he made up a plaster form—he made an inverted pyramid-thing that became the base of the head from the top of the face where the eyes are, right down to the neck, and he would glue everything onto that; then he’d paint several coats of latex on top of it. Some pieces were a quarter inch thick in spots. There were five heads altogether—four costume heads and one “hero” head for the close-ups, which was like a puppet head. It was opened in the back so he could make the eyes move. The eyes were just Styrofoam balls that he got over at good ol’ Frye Plastics. He put holes in the back of them so he could put his fingers in them to make the eyes move around. We never really got a chance to do that in the film. The fact that he made each one in that very special way, rather than creating a universal mold so he could just stamp them out, is why they’re all so different. Each one had its own personality because they were all separately built.

The veins were really cool. He took a piece of glass and he got a cake decorator and he thickened the rubber—I think he may have used talcum powder, at least it looked like talc to me—and he’d squirt those out onto the glass, let them dry, then peeled them off. They were flat on the bottom so it was really easy to glue them onto the masks. If you look at all the Saucer Men stills, you’ll see that they’re all different.

The brains themselves were Fiberglas. He made a Fiberglas shell from his plaster molds and glued the rubber on top of that. And, of course, there was the problem with the big, oversized brains that are in all the publicity pictures. Then you see the cabbage heads in the film—they’re really noticeably different. He just cut a pie-shaped wedge out of the Fiberglas when they told him the heads were too big, and pushed them back together. That’s all he could do—there wasn’t time to do anything else.

In a very effective sequence following the automobile accident in which Johnny and Joan run down a Saucer Man, the creature’s hand detaches from its body and seems to take on a life of its own. Outfitted with its own eyeball, the hand first disables the teenagers’ car by puncturing a tire, then makes its way into the passenger compartment where it attempts to attack them by working its way up the back of the seat. Burns explains how the hand was constructed and manipulated and provides some interesting insights into how this sequence was shot:

The [hands] were built over gardener’s gloves. They’re kind of squared off. He did the fingertips, I think, out of cardboard as a form and he painted latex on top, and then slipped them off. I’ve got a picture somewhere, where the fingers are drying on a wooden frame.

The hand used in the car was a puppet hand, really. Paul’s hand fit inside of it from underneath and the cut-off part of the wrist extended out over it. He was completely dressed in black. The part where the hand was climbing up the side of the car was just a double-exposure. They shot the car first, I believe, then covered it with black Doutene, then Paul, all dressed in black, went in and teetered the puppet hand on the window and acted like it was falling inside the car. Now there’s one real fast scene at the very end of that take where you can almost see his form—the shadowy form of his arm. It’s so quick you don’t see it much.

Inside the car—[the budget was so low] they couldn’t use a cutaway car that you could take the back off of, or whatever—so we shot that in a real car. I sat for something like an hour and a half doubling for Steve Terrell, and sat with the gal that doubled for Gloria Castillo, while Paul was like a pretzel in the back seat trying to climb that hand up the back of the seat. It was hot in there because they had these big lights hidden inside and poor Paul was in the back so he wouldn’t be seen. I had the easiest job in the world, I just sat there with my arm around a girl—simple, you know—but he had to do all this climbing up and all that kind of stuff. But the outcome was amazing! I thought the scene he did when the hand crawls across the road and [punctures] the tire was incredible—I thought that looked so cool!

The eyeball in the [puppet] hand could move, but they really didn’t use it in the film that much—in fact, I don’t think they used [it] at all. [The eyeball] was on a stalk underneath. It had a little dowel that Paul could use to make the eye move around.

The needles in the fingertips were just a [puppet hand] mounted on a little plunger. By pushing the plunger in there, little metal rods would come out. Paul had an ear syringe filled with water with tubes running to the hand and could squirt it and the water would come out to represent the alcohol. For that one close-up that they repeat in the film to show the needles coming out, he took straight pins and he figured out a way that when the water hit, it would push the pins to the surface and they would look really sharp.

When asked about the censorship of the time, and particularly how they got away with a graphically violent scene in which one of the Saucer Men grapples with and is gored by Larkin’s bull, Burns offered the following explanation:

The only way we got away with doing some of the gory special effects—like the Saucer Man getting his eye gouged—was because they were not human. They still even cut that, though. The way it worked in that particular scene with the Saucer Man and the bull, was that it was a Styrofoam eye and Paul drilled a hole in it and covered the hole with wax to blend it in. He was behind the [Saucer Man] head with a grease gun full of chocolate syrup. I had a fake bull’s head—it was just on a rod—and I took the horn and just pushed it into that hole that you couldn’t see because of the wax. I could see it, but no one else could. And I just wiggled it around a little bit and Paul squirted that gun and it just came gushing out, so they cut it. You see it start to gush, and then they cut away to something else. They thought that was a little too much. It really gushed out of there at first and just looked God-awful. Today anything goes, but that was 1957.

We got away with a lot if you think of some of the things that happened in the film, like the monster slime when the Saucer Man is under the front of the car. In that close-up [of the hand covered with slime from the dead Saucer Man] that’s not Frank Gorshin, that’s actually Paul’s hand. The slime was made out of Wild Root Cream Oil, which was a hair preparation at the time, chocolate syrup, lime Jell-o and glitter. That’s what he made the slime out of—and it looked great! Wah Chang—they were at the insert stage over at Howard Anderson’s [Studio]—he was shooting the close-ups for The Black Scorpion [Warner Bros., 1957], and he borrowed some of that slime and an ear syringe from us, because he forgot to bring some. So that stuff dripping out of the giant scorpion’s mouth was some of our slime. It was pretty neat when you think about it—”Oh, my God, it was in another movie!” Paul was a great one for using glitter to get the little highlights and weird effects. Do you remember Paul Dubov [as Radek] in Day the World Ended? He had that big, weird-looking streak on his face. That was just duo [surgical] adhesive—the kind of thing you use to put on false eyelashes—and Paul put some glitter on it to give it that kind of weird-looking texture. He was really good at figuring out that kind of stuff.

Being an extremely low budget affair produced on a constricted time schedule, most of it was filmed on a single soundstage. Bob Burns again provides the details:

If you didn’t look up into the grid and see the lights, you’d have really thought you were in the woods somewhere. The ground was uneven; they had those broken fence pieces. It was great. And they had risers that they built up so it had little uphill parts to the terrain. It wasn’t just a flat stage. It was filmed over at ZIV [Studios], on the biggest sound stage they had. The farmhouse was actually in the middle of the stage like it was suppose to be. In one corner of the stage were the police station and the café. They were right next to each other. The only thing that was on another set was the inside of the general’s apartment. That wooded area looked so neat, because it had all those trees and stuff, that it really looked like honest-to-God woods. It was the best indoor set I’ve ever seen of an outdoor [location]. The only outdoor shots were stock shots and shots of the cars driving by.

Today the concept of government secrecy and high-ranking cover-ups is something of a staple in American cultural mythology, but in June of 1957 when Invasion of the Saucer Men was released, the notion was relatively new. In the film, when the army fails to gain entry to the alien ship and instead blows it to smithereens by igniting a hidden fuse, the soldiers work diligently through the night to conceal the evidence of the alien presence. It would be sometime in the 1970s before UFO enthusiasts would, to any great degree, point to government conspiracies as a convenient rationale for why so little physical evidence survives to support the belief that UFOs are the vessels of visiting extraterrestrials. In this one regard, at least, Invasion of the Saucer Men was a film ahead of its time.

1958 was nearly as busy a year for Paul Blaisdell as the previous one, but just when his career was seemingly at its height there were signs, even for these marginal productions, that science fiction films were beginning to run out of steam. In 1958 Blaisdell’s work appeared in four films for AIP: the aforementioned War of the Colossal Beast (which was actually contained in footage recycled from The Amazing Colossal Man), Attack of the Puppet People, Earth vs. the Spider (a.k.a., The Spider) and How to Make a Monster. The first three were produced and directed by Bert I. Gordon and follow Gordon’s principle preoccupation with the theme of scale: giant people, little people and giant insects. The last one, How to Make a Monster, was produced by Herman Cohen and directed by Herbert L. Strock, and tells of a disenfranchised make up artist named Peter Drummond (Robert H. Harris) who gets booted out of his job at a film studio when the new management decides that audiences are no longer interested in monster movies. Using a special chemical in his make up base to gain hypnotic control over two young actors who’ve previously portrayed the teenage Frankenstein’s monster and the teenage werewolf (Gary Conway and Gary Clarke, respectively), Drummond uses the actors to kill off members of the studio’s new regime.

During the finale—the only scene of the film lensed in color—we see some Blaisdell’s own creations: Beulah, Cuddles, the Cat Girl, the Saucer Man and a Mr. Hyde mask that he created for Attack of the Puppet People, go up in flames. Not wanting to destroy his original masks, Blaisdell made wax castings of the particular characters that were earmarked to be photographed while on fire. His original mask for Cat Girl, however, was accidentally set ablaze by a technician, but the burning of the mask was not captured on film. More important than this regrettable loss, however, is how real life would eventually come to mimic the plotline of this film in its foretelling of the demise of Blaisdell’s own motion picture career.

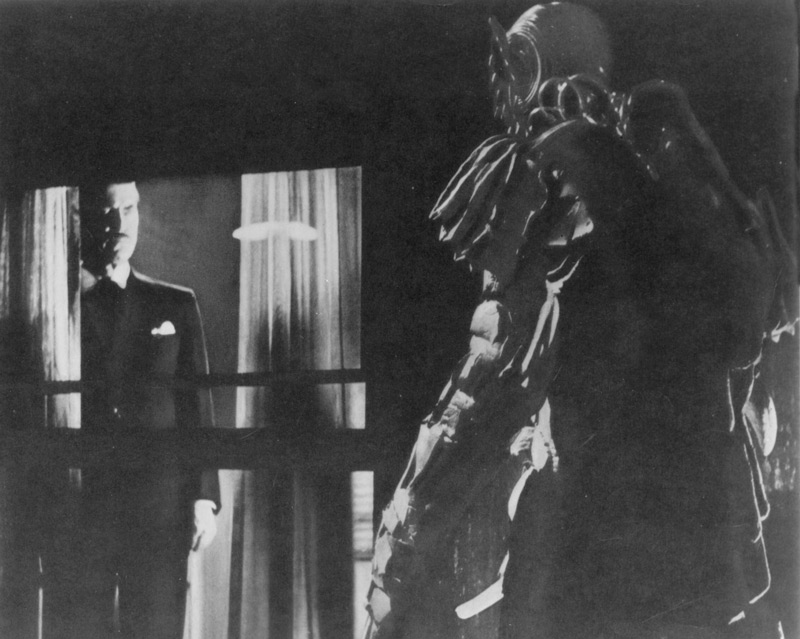

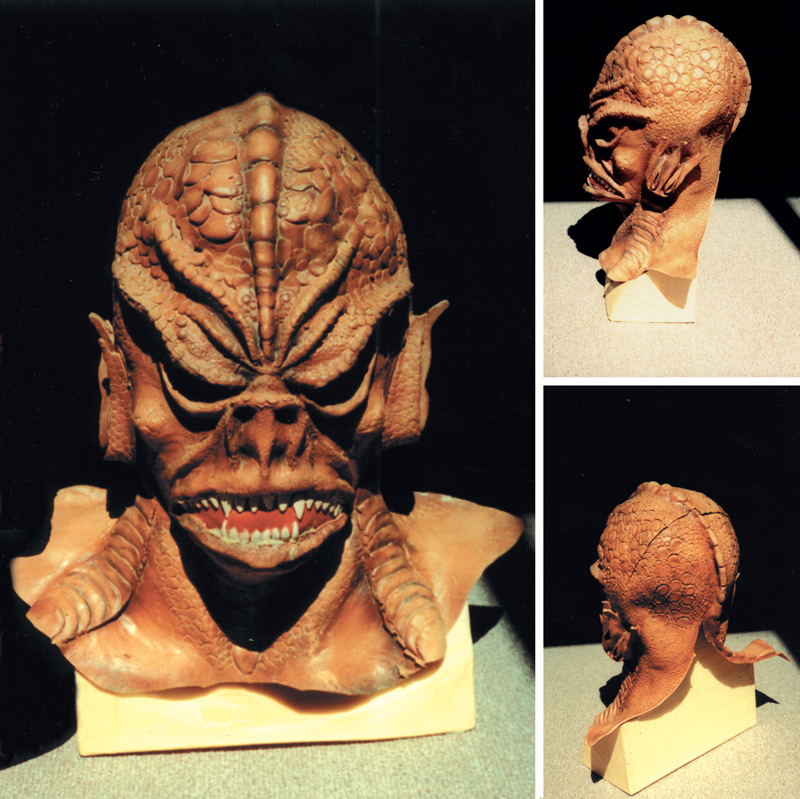

Paul Blaisdell worked on a fifth film released in 1958, It! The Terror from Beyond Space. With its intense, compelling story of astronauts within the confines of a spaceship pitted for survival against an unseen alien menace, it may well be the best motion picture of any with which Blaisdell’s name has been associated. Edward L. Cahn, with whom Blaisdell had worked on three previous pictures for AIP, directed the film, but the production crew was largely unknown to either of them. It! The Terror was made for Vogue Pictures, a tiny production company under the supervision of Robert E. Kent, and the movie was set for release by United Artists. Kent had also talked UA executive Edward Small into co-financing and releasing another SF/horror film, Curse of the Faceless Man, with which It! The Terror was later double-billed. This second feature was also directed by Eddie Cahn and scripted by Jerome Bixby, but the costume for its title monster, a two thousand year old resurrected slave from ancient Pompeii, was designed and built by Charles Gemora, the Phillipino artist who had created the three-fingered Martian for George Pal’s science fiction classic, The War of the Worlds (Paramount, 1953).

While AIP had been exceedingly frugal, and at times frustratingly schedule conscious, to stalwarts like Eddie Cahn and Paul Blaisdell there had at least been a compensating sense of family. Blaisdell found that these new circumstances afforded little by way of camaraderie and the experience at UA had been sufficiently unpleasant for it to have been a factor in eventually souring his attitude toward the motion picture industry.

It! The Terror from Beyond Space was release on August 7th and it came and went without much fanfare, but it would be cited in discussions in the late 1970s as the inspiration for the hit movie, Alien (20th Century-Fox, 1979) and would subsequently enjoy a minor renaissance in a variety of home video formats. While there is little question about the affinity between the two, no one associated with the making of Alien has yet publicly acknowledged the connection. It! The Terror was produced on a veritable shoestring, yet it is superior in some ways to its famous—and vastly more expensive—offspring.

Scripted by the noted science fiction author Jerome Bixby (1923-1998), the movie tells the tale of an ill-fated expedition to Mars and of a recovery ship that ventures to the Red Planet to retrieve the mission’s sole survivor, Lt. Edward Carruthers (Marshall Thompson). Carruthers, a pioneering figure in space exploration, claims that his crew was savagely attacked and slain during a sandstorm in the Martian desert by a strange, shadowy figure. Finding no evidence of the creature, the crew of the recovery ship packs up and heads for Earth unaware that the alien, or another of its species, has stowed away onboard. Carruthers, now under suspicion of having murdered his fellow crewmembers, is brought back under custody. That is, until the return voyage when something largely unobserved begins to systematically kill off members of the crew by making its way through the ship’s ventilation system. The victims are found with their bones pulverized and are completely drained of all bodily fluids. On the arid deserts of Mars, the dominant species has evolved into a race of moisture vampires with an indiscriminate craving for liquids. They also possess massive lungs to breathe the thin air of their home world, and the alien’s consumption of the ship’s oxygen supply gives the surviving crewmembers a clue to eventually overcoming the intruder.

Marshall Thompson was the film’s sole bankable star (though most of his career had been limited to small supporting roles in big pictures and starring roles in “B” films and on TV), but the supporting cast—with the exception of Kim Spalding as the rescue ship’s commander, Col. James Van Heusen—is comprised of solid character actors, such as Ann Doran and Dabbs Greer. They portray the husband and wife science team of doctors Mary and Eric Royce. The noted athlete and stuntman Ray “Crash” Corrigan (1902-1976), who had at this particular point in his life yielded to the deprivations of acute alcoholism, portrayed “It.” Corrigan’s passive-aggressive behavior and difficulties in navigating around the set in costume while intoxicated, threatened to slow down production, but were apparently not sufficient to get him fired off the picture. As a result, a few flaws made their way into the final cut of the film.

One of these flaws came early on when Corrigan refused to don the restrictive headpiece of the monster costume for a scene in which only the creature’s cast shadow on the ship’s bulkhead would be seen. The silhouette of Corrigan’s unmistakably human head does not match that of the creature’s when the creature’s appearance is finally revealed to us about halfway through the film. Bob Burns, who again assisted Paul Blaisdell during his limited access to the set, tells of another moment that remains immortalized in celluloid:

Corrigan was looking up at the camera in one of the film’s few close-up shots of the monster, and he’s suppose to be listening to the people up in the top deck. He’d been in the suit about an hour, and with his chin actually sticking out, when he would move that mouth at all it would start to pull the eyeholes away from his eyes. Eddie [Cahn] shouted out to him, “Lift your head. I can’t see your eyes, lift your head up!” Corrigan took it literally and you suddenly see this big claw come up and he lifts the [monster mask’s] head up! They just left it in the film!

Burns refers to Corrigan’s chin sticking out through the creature headpiece. This situation arose when the producers failed to inform Paul Blaisdell that he would not be donning the monster suit himself, but that Ray Corrigan had instead been hired for the role. Burns elaborates:

Paul had real problems with It! The Terror, since that was a totally different studio, and the only person he knew there was Eddie Cahn. That was a whole different thing and that was a very, very sad and nasty experience for him. He was not happy with that at all. They treated him like dirt there. He didn’t want to go back. In fact when they told him they really didn’t need him on the set and he left, then two days later he gets this call: “Oh, my God! You’ve got to come back! We can’t get this guy into the suit! We don’t know how to fix him!”—and, of course, the head not fitting on [Corrigan] right and all—so he had to go back over and do it. And he would, because he was a credible man. He wasn’t going to let it go bad.

When Paul first started sculpting the head he thought he was going to play the monster as he always did, and that’s why he used Jackie’s cast of his own head. By the time he got it just about done, just about ready to make a mold of it, that’s when he heard, “Oh, no, we’re using ‘Crash’ Corrigan.” Oh, that’s nice! Crash was half again as big as Paul. Eddie Small, the head of [UA’s] production company, just wanted to use [Corrigan]; just wanted to give him some work. They’d been old buddies from way back, I guess. Eddie Small…was a typical, cocky producer—a cigar chomping kind of guy, you know.

When Paul did the head they said, “Oh, it’ll fit, don’t worry about it.” Corrigan, for some reason, didn’t want to come in for a fitting, so he just sent over a pair of long johns. Paul just stuffed them with newspaper and built the whole suit over that.

When the headpiece was placed on Corrigan’s massive head, the actor’s chin protruded through and distorted the mask’s mouth. Blaisdell arrived on the sound stage after the panicked phone call with a set of hastily assembled lower teeth for the creature’s mouth, which he glued into position on the mask. With the actor’s chin painted red to look like the monster’s enlarged tongue, and the lower teeth in position to complete the illusion, Corrigan was quickly outfitted and was ready to go back to work. Once again, Blaisdell’s resourcefulness and willingness to co-operate saved the day.

Bob Burns again describes the details of the creature suit’s construction, provides an example of Blaisdell’s less than cordial treatment on the set and comments on Edward L. Cahn, his highly efficient working style and his direction of It! The Terror from Beyond Space:

“It” was the only monster suit that Paul ever built molds for. I have the one mold, for the head. He made probably thirty different texture patterns of scales. He and Jackie made them all up and glued then on one at a time, just like they did for the She-Creature, basically, and made the whole suit that way. The claw parts were made of white pine, covered with latex over heavy garden gloves. The feet were sculpted and molded. It’s the only monster that he actually sculpted from the ground up out of negative molds.

Paul built an extra arm so Corrigan wouldn’t have to put the suit on for those scenes of the monster coming up through the hatches. He took it over to the studio one day and I guess the assistant director was there and he looked at Paul and asked, “Who the hell are you?” Paul tried to explain that he’d made this extra arm and the guy said, “Just leave it over there and get out of here!” It was just like Paul to do more than he was asked and he took pity on Corrigan, knowing he was uncomfortable in the suit. Paul was very thoughtful that way.

Eddie Cahn, he knew how to shoot It! The Terror from Beyond Space. It looked very effective. It was a really very well done film for what it was. I think it was shot in about twelve days. It had a longer shooting schedule than most of the films Eddie worked on. He also knew the limitations of Crash [brought on by his drinking], and so he kept that in mind. Eddie Cahn, I’ve got to say, was probably one of the best directors I’ve ever seen work—and especially with those short shooting schedule things, where he didn’t have any time. He did his homework every night. He came in and he knew exactly what set-ups he wanted. And, if possible, he could do forty set-ups in a day. He’d just move on. He was even better at it than Roger Corman. Of course, he’d been around a lot longer. He used to do a whole lot of those “B” westerns.

The years 1957 and ’58 marked the most productive and prosperous period of Paul Blaisdell’s film career. In 1959, however, his motion picture commissions began to dwindle, and over the next few years they dropped precipitously. During his all-too-brief heyday, however, three significant events influenced the production of science fiction films and eventually impacted Blaisdell’s life.