An article on the UCSD website was released recently and details the findings of a study performed by Nicholas Christenfeld and Jonathan Leavitt of UC San Diego’s psychology department. The article, which will be released in an upcoming issue of the journal Psychological Science, appears to claim that “spoilers” are no big deal and that people who know the outcome of a given story actually might enjoy it more.

Although this article is only summary of their findings, their claims seem highly dubious. In fact, based on what the article tells us about the research conducted in regard to spoilers, I’ll go ahead and say they are totally wrong, for a lot of reasons.

According to the article on the UCSD website, the experiment was performed with 12 short stories, 4 each in 3 specific categories: ironic-twist, mystery, and literary. The mistake in this experiment is already apparent. In terms of spoilers, literary stories are far less prone to being “ruined” by knowing the ending, thus that category shouldn’t have even been included. A study about spoilers should address stories people actually worry about having ruined for them, and quite frankly, when I talk about Raymond Carver (which is a lot!) nobody runs over asking me to please, please not tell what happens in the “The Bath.” (Spoiler: A kid dies.)

Literary short stories often contain mysteries and ironic twists, but the stories selected here for this category don’t rely on those twists. In the introduction to the latest posthumous Kurt Vonnegut collection, Dave Eggers referred to these types of stories as “mousetrap stories.” The stories in the literary category like “The Calm” by Raymond Carver or “Up at the Villa” by W. Somerset Maugham are not these kinds of stories. I would argue instead, the revelation of plot is not why people read and enjoy these stories. What we talk about when we talk about spoilers is not Raymond Carver or W. Somerset Maugham. So, let’s not include those in a study. (Also, I’m forced to assume they mean M. Somerset Maugham because they listed a story called “Up at A Villa” which is actually a Robert Browning poem, the full title of which is “Up at a Villa–Down in the City”, whereas “Up at THE Villa” is a story by Maugham. If they did mean the Browning poem, I’d be fascinated to know their opinions on poem spoilers.)

Okay, so one of their “groups” is disqualified. What about mysteries and “ironic twist” stories? I’d agree with their findings on some level that mysteries or ironic twists might not be spoiled by knowing the ending. Half the fun of an Agatha Christie mystery or even a Sherlock Holmes story is seeing how the detectives solve the case rather than being presented with the answers. But that is a pretty blithe assertion. A classic whodunit is called a whodunit for a reason. We want to know, quite simply, whodunit? Also in my view, when people read a traditional mystery they are aware of many possible “solutions” already. Even if a reader sees a solution coming a mile away, they are still satisfied when proven correct. The study doesn’t take this aspect of an enjoyment into account.

The study also present a category of “ironic/twist” stories, with “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge” being the most obvious choice. Here, I just flatly disagree with the implication that someone would enjoy this “kind” of story more if they already know the ending. In essence, this story employs the same basic device as a Twilight Zone episode insofar there is a twist. (Spoiler alert: the character is imagining his escape in the split second that his hanging takes place.)

Now, I can’t disagree that some people said they enjoyed the story more by already knowing the ending because people derive enjoyment differently on a person-to-person basis. But this study implies that the difference between being spoiled and not being spoiled is negligible, when that is clearly untrue. For example, the best way to enjoy the “Twilight Zone” episode “Time Enough at Last” is to have no knowledge of the ending. If you know it already, the irony can build in your mind the entire time, and still have a good time, but that enjoyment is simply not the same as the intended enjoyment.

Further, because the study cannot conduct an experiment on the SAME PERSON reading “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge” once with advanced knowledge, and once without advanced knowledge we can’t really measure or even prove a relative enjoyment or not. (This even if we leave out different kinds of enjoyment!) If we had a parallel dimension version of the reader, then we might have a real control group. But without that the entire study is relativistic at best.

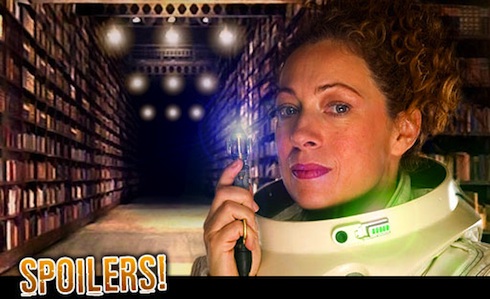

Finally, I’ll go ahead and say it, the conclusions are shoddy because the media used to conduct the experiment is the wrong kind. Short stories are wonderful and I think they’re the bread and butter of civilization. But they’re often not what we talk about when we talk about spoilers. We talk about TV, movies, comics, book series, and so on. We talk about the sorts of things people chatter about in bars, on internet message boards, on Twitter, on the street, in the subway, and at parties. No one is going around cocktail parties ruining the ending of “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge” for you, but they might be telling you who the final Cylon is on Battlestar Galactica or more recently, the real identity of River Song on Doctor Who. This kind of media is inherently different than several decades old short stories. Quite simply, you can’t spoil Agatha Christie in the same way that you can spoil the latest episode of Mad Men. Television is an intrisically different media than print because it is fleeting and temporary. The kinds of enjoyment we get from it is not the same as the kind we get from the written word. Yes, the structures are similar in terms of plots, but the way we perceive it and react to it is different. The study doesn’t take this into account at all, and as such brings nothing relevant to the discussion of spoilers. In short, these are the wrong spoilers to be studying.

There are a lot of types of enjoyment, and the one that seems to have been neglected is the thrill of being surprised. The folks at UCSD don’t seem to have even considered that when they conducted this study, which is the final reason why I think their conclusions are highly questionable.

I’m willing to see what the rest of the actual study claims, but for now it seems to be simply addressing the wrong media, missing the relevance of mysteries, assuming there is one kind of enjoyment, and failing to recognize that they can’t have a control group because the same person can’t experience a story two different ways. Is this even science?

Ryan Britt is a staff writer for Tor.com. He is spoiled on every single one of his own articles for Tor.com, which really sucks sometimes.