Welcome to Genre in the Mainstream, a weekly column in which we jump out of our science fiction and fantasy rocketship and parachute into the bizzaro world of literary fiction. Sometimes what we find in this alternate reading dimension are books and authors that just might appeal to readers of science fiction and fantasy. We’re not claiming these books science fiction or fantasy necessarily, but we do think there’s a good chance Tor.com readers will like them! This week, we discover how the most efficient form of time travel might not be a phone box or a Delorean, but rather a good-old fashion bump on the head in Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court.

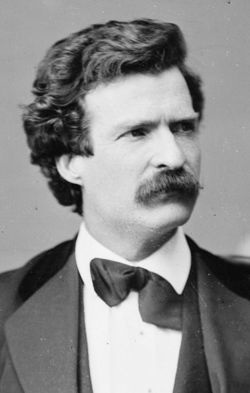

Though it was Arthur C. Clarke who doled out the maxim “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic” it was Mark Twain who originally brought the firestick to the ignorant savages of the past. Though certainly not the first work of English-language literature to deal with time travel, A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court does predate H.G. Well’s The Time Machine. But unlike The Time Machine, Twain takes his protagonist backwards rather than forwards, and features an unwitting everyman time traveler in opposition to Well’s intrepid inventor and explorer.

Twain gives us Hank Morgan, a man who resides in the American Northeast during the 19th century who, after suffering a bump on the head, wakes up in the middle of Camelot in the year 528. Almost immediately, by virtue of Hank seeming out-of-place, he is promptly imprisoned and indentified by Merlin as someone who needs to be burned at the stake. Though he’s initially depicted as a philistine, we quickly learn Hank is a 19th century version of MacGyver crossed with Hermione from Harry Potter. He seems to be able to make makeshift technology out of nothing and also possesses a handy slew of trivia in his 19th century brain, including the fact that a solar eclipse is coming up. Hank is a little off on the exact timing of the eclipse, but still manages to parlay this knowledge into making it look like he can out-sorcer the sorcerer. From there, Hank puts events into motion that involve a secret army, going undercover among the peasants, and accidentally getting sold into slavery with an incognito King Arthur. The novel eventually culminates with the Catholic Church sending 30,000 knights to take out Hank, who eventually refers to himself as “The Boss.” With homemade gatling guns and a small band of soldiers, Hank basically brutally slaughters the attacking knights. In a kind of Richard III move, Hank wanders the battlefield thereafter wracked with guilt, only to get stabbed.

Twain gives us Hank Morgan, a man who resides in the American Northeast during the 19th century who, after suffering a bump on the head, wakes up in the middle of Camelot in the year 528. Almost immediately, by virtue of Hank seeming out-of-place, he is promptly imprisoned and indentified by Merlin as someone who needs to be burned at the stake. Though he’s initially depicted as a philistine, we quickly learn Hank is a 19th century version of MacGyver crossed with Hermione from Harry Potter. He seems to be able to make makeshift technology out of nothing and also possesses a handy slew of trivia in his 19th century brain, including the fact that a solar eclipse is coming up. Hank is a little off on the exact timing of the eclipse, but still manages to parlay this knowledge into making it look like he can out-sorcer the sorcerer. From there, Hank puts events into motion that involve a secret army, going undercover among the peasants, and accidentally getting sold into slavery with an incognito King Arthur. The novel eventually culminates with the Catholic Church sending 30,000 knights to take out Hank, who eventually refers to himself as “The Boss.” With homemade gatling guns and a small band of soldiers, Hank basically brutally slaughters the attacking knights. In a kind of Richard III move, Hank wanders the battlefield thereafter wracked with guilt, only to get stabbed.

The great thing about this novel is it sort of seems like Twain is gearing up for his latter work, the really dark fantastical fiction novel Letters from the Earth. In this novel, he handles science fiction in way that has been influential for years. It’s not so much that Twain is obviously evoking the Prometheus myth of bringing fire to a society that can’t handle it, it’s that he’s also making his version of Prometheus (Hank) a guilty and relatable character. Hank isn’t an anti-hero, but he’s not quite a villain either, in short, he makes certain decisions that lead to other decisions that eventually spin out of control. He may not be as likeable as Twain’s other famous characters like Tom Sawyer or Huck Finn, but Hank is certainly as realistic.

In a sense, Hank is sort of like a dark version of Kirk in the 60s Star Trek. In all instances when the Enterprise encounters an alien planet where the people haven’t gotten their technological acts together, someone will point out that the Enterprise can just lay waste to planet from orbit and show everyone who’s boss. But, Kirk usually ends up giving speeches involving how he won’t kill “today.” Human barbarism and desire to destroy in order to maintain power is treated by Twain and 60s Trek writers the same way. The only difference is Kirk almost always makes the right decisions and resists the impulse to impose his superior knowledge and technology on “primitives.” Hank does the opposite, and his punished by having to actually live with the guilt of basically being a mass murderer.

The best science fiction will put characters in a situation in which technology’s interaction with humanity has created some kind of ethical dilemma. In Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court the main character creates a situation for himself in which technology is interacting with humanity with dubious moral implications. Twain was not only one America’s greatest writers ever, but also created a blueprint for the themes science fiction writers would be following for the next 100 plus years to come.

It would be interesting to see what Twain would write about if he got bumped on the head and woke up in our century.

Ryan Britt is a staff blogger for Tor.com. As a confused child, Ryan believed that Mark Twain had also written the episode of Star Trek:The Next Generation in which he appears.