Along with the thrice-filmed (and oft-plundered) I Am Legend, “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet” is one of Matheson’s best-known works, the tale of an airline passenger doubting his sanity when he alone sees a gremlin on the wing, damaging one of the engines. Since debuting in the anthology Alone by Night (1961), Matheson’s story has been reprinted many times, recently toplining Tor’s eponymous collection, and he adapted it for two incarnations of The Twilight Zone, first in the fifth and final season and then as a segment of the ill-fated 1983 feature film. Perhaps the best-known episode (sometimes misattributed to creator/host Rod Serling), “Nightmare” has spawned homages on The Simpsons, Saturday Night Live, Futurama, 3rd Rock from the Sun, and others.

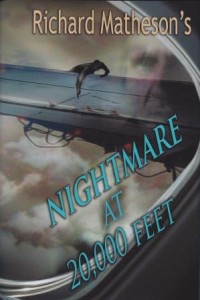

Richard Matheson’s Nightmare at 20,000 Feet is the latest impressive Matheson limited edition from Gauntlet Press, marking this classic chiller’s fiftieth anniversary and encompassing all of its manifestations in word and image. Included are not only Matheson’s story and teleplay, but also director George Miller’s rewrite of his screenplay for Twilight Zone—The Movie, the storyboards for that segment, photos, and other goodies. As usual, Gauntlet has lined up a selection of heavy hitters to contribute, such as Richard Donner and William Shatner, respectively the director and star of the television version; Matheson’s son, famed author and screenwriter Richard Christian Matheson; Serling’s widow, Carol; and Farscape and Alien Nation creator Rockne S. O’Bannon.

Tony Albarella, who has masterfully edited Serling’s Twilight Zone scripts (two of them based on Matheson stories) for Gauntlet, sets the stage with his introductory essay “Fright Plan.” This takes the reader from the story’s inspiration on an actual flight through to the present day, when “it has been referenced by rock bands, spoofed in countless movies and televisions shows, and merchandised as trading cards and action figures.” Albarella observes that the protagonist has a different name each time—Arthur Jeffrey Wilson in the story, Robert Wilson in the show, John Valentine in the film—but he omits a curious anomaly: Bob refers to Mrs. Wilson as “Julia,” yet the script credits her as “Ruth,” the name of Matheson’s wife and many of his female characters.

With Matheson’s Twilight Zone scripts having been published in multiple editions, the material from Twilight Zone—The Movie is clearly of greatest interest to collectors, and the storyboards enable readers to “watch” the segment from start to finish, minus John Lithgow’s frantic turn as Valentine. Albarella notes that the greatest change in Miller’s uncredited rewrite (which is dated September 30, 1982, and reveals that the segment was intended to be second rather than last) was to remove the fact of Valentine’s prior mental instability, which worked so well in the television version. This makes the character a hysterical white-knuckle flier who, as Matheson lamented, “was too over-the top. He starts at one hundred percent so there’s no place left for him to go.”

Of the celebrity essays, Donner’s is the most substantive, detailing the technical challenges faced in filming the episode; Carol Serling recalls her husband’s warm friendship with Matheson, and R.C. points up the tale’s Jungian aspects. Welcome though they are, these contain a few memory lapses, e.g., Serling’s stating that “way before The Twilight Zone came on the air [in 1959], Rod picked up a short story collection of Richard’s called Shock,” published in 1961. Shatner’s brief but enthusiastic encomium asserts, “Live television with all its passions and innovations and all its overwhelming problems set the stage for Richard who solved many of those moments by the dint of his prodigious talents,” yet I am unaware that he had any involvement in live television.

The book opens with Rod Serling’s oft-quoted account (from a 1975 class lecture less than three months before his death) of how he arranged to have a huge blow-up of the gremlin stuck outside Matheson’s window for a flight they were making together, only to have the prop wash blow it away before he could see it. Matheson has told me this story was apocryphal, and yet even the verifiable facts surrounding “Nightmare” are sufficient to enshrine it as a perennial pop-culture favorite. As O’Bannon—part of an entire generation of writers and filmmakers to be influenced by Matheson’s work—writes in his essay, and this volume ably demonstrates, “there is no better example of Richard Matheson as the master story watchmaker than ‘Nightmare at 20,000 Feet.’”

Matthew R. Bradley is the author of Richard Matheson on Screen, now in its third printing, and the co-editor—with Stanley Wiater and Paul Stuve—of The Richard Matheson Companion (Gauntlet, 2008), revised and updated as The Twilight and Other Zones: The Dark Worlds of Richard Matheson (Citadel, 2009). Check out his blog, Bradley on Film.