Daniel Abraham has a very thought-provoking article on genre on his blog, I commend it all to your attention. He talks about what genres are, and he says:

I think that the successful genres of a particular period are reflections of the needs and thoughts and social struggles of that time. When you see a bunch of similar projects meeting with success, you’ve found a place in the social landscape where a particular story (or moral or scenario) speaks to readers. You’ve found a place where the things that stories offer are most needed.

And since the thing that stories most often offer is comfort, you’ve found someplace rich with anxiety and uncertainty. (That’s what I meant when I said to Melinda Snodgrass that genre is where fears pool.)

I think this is brilliant and insightful, and when he goes on to talk about romances, westerns, and urban fantasy I was nodding along. Genre is a something beyond a marketing category. Where fears pool. Yes. But when he got to science fiction I disagreed just as strongly as I’d been agreeing before, because in that sense—the sense in which “a particular story (or moral or scenario) speaks to readers” science fiction isn’t one genre, it’s a whole set of different ones, some of them nested.

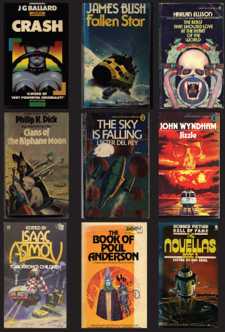

It’s always easiest to define a genre when it’s over. I’ve talked here before about the cosy catastrophe, a genre that’s science fiction except for when it was a huge bestselling genre briefly. They really are a genre in that sense—they are essentially variations on a theme. They fit a pattern. The really interesting thing about them for me is that I was massively invested in them as a teenager, I couldn’t get enough of them, and that twenty years before that they were a huge bestselling mainstream phenomenon—everybody couldn’t get enough of them. And just as I grew out of it, so that my interest in them now is primarily nostalgic, so did everyone else. They really clearly were where “fears pooled,” and they were fears about nuclear war and about needing to have a fair deal for people of every class, and they were consolatory comfort in that they said a few nice people would survive and build a better world, and that would be us.

I think there are other genres like this within science fiction. There’s the “wish for something different at the frontier” genre—Hellspark fits into that too, and Lear’s Daughters. There’s the “American revolution in space” genre. There’s the “Napoleonic war in space” genre. There’s my favourite “merchanters, aliens and spacestations” genre. There are others we could identify—there are some I’ve been thinking we don’t see much any more, like the “computer becomes person” genre and “cold war in space.” The thing about these is that they are doing variations on themes. You know what’s going to happen even when you don’t know what’s going to happen. You know the shape of the story in the same way you do in a mystery or a romance. And whether or not they’re about fears pooling, they’re about getting the same fix.

But science fiction also contains this huge set of things that don’t fit into subgenres, that you can’t fit into a Venn diagram of overlapping tropes, that are weird outliers—and yet they’re clearly science fiction. I’ve been thinking about this recently because I’ve been looking at Hugo nominees. If you look at the Hugo nominees for any year, and remove the fantasy, what you have left is four or five excellent books that don’t look as if they came from the same universe, never mind delivering the same “story or moral or scenario.” Here, look at this year:

- The City & the City, China Miéville (Del Rey; Macmillan UK)

- The Windup Girl, Paolo Bacigalupi (Night Shade)

- Boneshaker, Cherie Priest (Tor)

- Julian Comstock: A Story of 22nd-Century America, Robert Charles Wilson (Tor)

- Palimpsest, Catherynne M. Valente (Bantam Spectra)

- WWW: Wake, Robert J. Sawyer (Ace; Gollancz)

Look at last year:

- Anathem, Neal Stephenson (Morrow; Atlantic UK)

- Little Brother, Cory Doctorow (Tor)

- Saturn’s Children, Charles Stross (Ace; Orbit)

- Zoe’s Tale, John Scalzi (Tor)

Look at 2008:

- The Yiddish Policemen’s Union, Michael Chabon (HarperCollins; Fourth Estate)

- Brasyl, Ian McDonald (Gollancz; Pyr)

- Halting State, Charles Stross (Ace)

- The Last Colony, John Scalzi (Tor)

- Rollback, Robert J. Sawyer (Analog Oct 2006 – Jan/Feb 2007; Tor)

Keep going back as far as you like, you can use the same Locus list I’m using. Here, have 1970:

- The Left Hand of Darkness, Ursula K. Le Guin (Ace)

- Bug Jack Barron, Norman Spinrad (Avon)

- Macroscope, Piers Anthony (Avon)

- Slaughterhouse-Five, Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. (Delacorte)

- Up the Line, Robert Silverberg (Ballantine)

What Abraham sees as fracturing is what I see as the long term strength of the genre as…not actually being a genre in his sense of the word.

Science fiction is a broadly defined space in which it’s possible to do a whole lot of things. Some science fiction readers do only want their subgenre doing the same thing—and that worries me a bit, because I think the real strength of the genre has always been that there are all these hugely different things out there and yet they are in dialogue with each other. Because that’s the other meaning of a genre, genre as writers group, where the works are sparking off each other. Science fiction really is a genre in that sense. It has reading protocols. It assumes a readership that’s read other science fiction. And it assumes it’s read other different science fiction.

You can look at the things Abraham thinks science fiction is fracturing into and they’ve always been there, and they have always fed into each other.

However, if there’s a thing paranormal fantasy readers get from reading that does something with their fears (and similarly for romance readers and mystery readers, etc) then the thing that I think science fiction readers get from reading lots of SF is the deep conviction that this world is not the only world there could be, that the way the world is is not the only way it can be, that the world can change and will change and is contingent. You don’t get that from reading any one book, or any one subgenre, you get it from reading half a ton of random science fiction.

I think there’s another thing we get, which is the urge to say “Hey, will you look at that!” Habitual SF readers want to talk to other people about what they have read—that’s where fandom came from, and it’s something I’ve noticed in people who read a lot of science fiction but have no connection with organized fandom. I think the other genres that cluster around SF and which science fiction readers also read—fantasy of various kinds, historical fiction, mystery, science essays—share this characteristic to greater or lesser degrees.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published eight novels, most recently Lifelode, and two poetry collections. She has a ninth novel coming out in January, Among Others, and if you liked this post you will like it. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.