I wanted to fall in love with this book. Halfway through, I almost did fall in love with this book.

And then I read the rest of it.

The Silver Princess in Oz brings back some familiar characters—Randy, now king of Regalia, and Kabumpo, the Elegant Elephant. Both are experiencing just a mild touch of cabin fever. Okay, perhaps more than a mild touch—Randy is about to go berserk from various court rituals and duties. The two decide to sneak out of the country to do a bit of traveling, forgetting just how uncomfortable this can be in Oz. Indeed, one of their first encounters, with people that really know how to take sleep and food seriously, almost buries them alive, although they are almost polite about it. Almost:

“No, no, certainly not. I don’t know when I’ve spent a more delightful evening,” Kabumpo said. “Being stuck full of arrows and then buried alive is such splendid entertainment.”

A convenient, if painful, storm takes them out of Oz and into the countries of Ix and Ev, where they meet up with Planetty and her silent, smoky, horse. Both of them, as they explain, are from Anuther Planet. (You may all take a moment to groan at the pun.)

The meeting with the metallic but lovely Planetty shows that Ruth Plumly Thompson probably could have done quite well with writing science fiction. Following L. Frank Baum’s example, she had introduced certain science fiction elements in her Oz books before, but she goes considerably further here, creating an entirely new and alien world. Anuther Planet, sketched in a few brief sentences, has a truly alien culture: its people are birthed full grown from springs of molten Vanadium, and, as Planetty explains, they have no parents, no families, no houses and no castles. In a further nice touch, Planetty’s culture uses very different words and concepts, so although she (somewhat inexplicably) speaks Ozish (i.e., English) it takes Randy and Kabumpo some time to understand her. And it takes Planetty some time to understand them and the world she has fallen into, although she finds it fascinating.

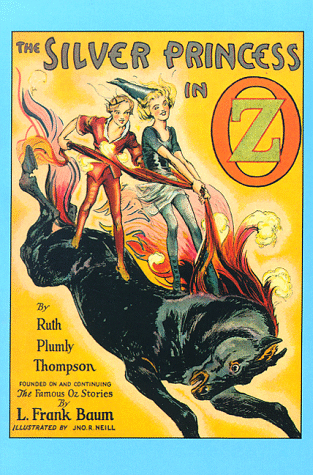

Despite voicing some more than dubious thoughts about marriage earlier in the book, Randy falls in love with Planetty almost instantly. But Planetty turns out to be Thompson’s one romantic heroine in no need of protection. Planetty is even more self-sufficient than Mandy had been, and considerably more effective in a fight than Randy or Kabumpo (or, frankly, now that I think about it, the vast majority of Oz characters), able to stand on the back of a running, flaming horse while turning her enemies into statues. (She’s also, in an odd touch, called a born housewife, even though she’s never actually seen a house before, and I have no idea when she had the time to pick up that skill, but whatever.) Perhaps writing about Handy Mandy in her previous book had inspired Thompson to write more self-reliant characters. Planetty’s warrior abilities and self-reliance only increase Randy’s love, and the result is one of the best, most realistic, yet sweetest romances in the Oz books.

All of it completely ruined by a gratuitous and, even for that era, inexcusably racist scene where the silvery white Planetty, mounted on her dark and flaming horse, mows down a group of screaming, terrified black slaves brandishing her silver staff. She merrily explains that doing this is no problem, since this is how bad beasts are treated in her home planet, so she is accustomed to this. (Her metaphor, not mine.) By the time she is finished, Planetty has transformed sixty slaves into unmoving metal statues. The rest of the slaves flee, crying in terror. Kabumpo makes a quiet vow to never offend Planetty, ever.

Making the scene all the more appalling: the plot does not require these characters to be either black or slaves in the first place. True, keeping slaves might make the villain, Gludwig, seem more evil, but since Jinnicky, depicted as a good guy, also keeps black slaves, I don’t think Thompson intended the implication that slaveholders are evil. The transformed characters could easily be called “soldiers,” and be of any race whatsoever—literally of any race whatsoever, given that they are in the land of Ev, which is filled with non-human people. I’m not sure that the scene would be much better with that change, but it would at least be less racist.

But I don’t think the racism is particularly accidental here. As we learn, this is a slave revolt, with a black leader, one firmly quelled by white leaders. (Not helping: the black leader, Gludwig, wears a red wig.) After the revolt, the white leaders do respond to some of the labor issues that sparked the revolt by arranging for short hours, high wages and a little house and a garden for the untransformed slaves; the narrative claims that, with this, the white leaders provide better working conditions. But it is equally telling that the supposedly kindly (and white) Jinnicky faced any kind of revolt in the first place. (The narrative suggests, rather repellently, that Gludwig easily tricked the slaves, with the suggestion that the slaves are just too unintelligent to see through him.) Even worse, Jinnicky—a supposed good guy—decides to leave the rebel slaves transformed by Planetty as statues, using them as a warning to rest of his workers about the fate that awaits any rebels. That decision takes all of one sentence; Jinnicky’s next task, bringing Planetty back to life (she has had difficulties surviving away from the Vanadium springs of her planet), takes a few pages to accomplish and explain.

It is, by far, the worst example of racism in the Oz books; it may even rank among the worst example of racism in children’s books, period, even following an era of not particularly politically correct 19th and early 20th century children’s literature. (While I’m at it, let me warn you all away from the sequels in the Five Little Peppers series, which have fallen out of print for good reason.) The casual decision—and it is casual, making it worse—to leave the black slaves as statues would be disturbing even without the racial implications. As the text also clarifies, the slaves were only following orders, and, again, let me emphasize, they were slaves. With the racial implications added, the scenes are chilling, reminiscent of the Klu Klux Klan.

(Fair warning: the illustrations here, showing the slaves with racially exaggerated facial features, really do not help. These are the only illustrations by John Neill I actively disliked. If you do choose to read this book, and I have warned you, and you continue on to the end instead of stopping in the middle, you may be better off with an unillustrated version.)

Even aside from this, Silver Princess is a surprisingly cruel book for Thompson, filled with various scenes of unnecessary nastiness: the aforementioned arrows, a group of box-obsessed people attacking the heroes, a fisherman attacking a cat, and so on. (And we probably shouldn’t talk about what I think about Ozma allowing Planetty to walk around Oz with a staff that can turn anyone into a statue, except to say, Ozma, having one set of rules for your friends and another set of rules for everyone else is called favoritism, and it’s usually not associated with an effective management style).

But in the end, what lingers in the memory are the scenes of white leaders crushing a black slave revolt, leaving the slaves as statues, all in one of the otherwise most lighthearted, wittiest books that Thompson ever wrote.

This matters, because so many later fantasy writers (think Gene Wolfe and Stephen Donaldson, for a start) grew up reading and being influenced by the Oz series, and not just the Baum books. It matters, because even in the 1980s, as the fantasy market expanded, it could be difficult to find children’s fantasy books outside of the Oz series (things have radically improved now; thank you Tolkien and Rowling and many others.) It matters, because children and grownups hooked on the very good Baum books and some of the Thompson books may, like me, want and need to read further.

It matters, because I like to think that the Oz books, especially those written by Baum (and the McGraws), with their messages of tolerance and acceptance and friendship despite superficial appearances, had a significant, positive effect on me while I was growing up. They gave me hope that I, a geeky, socially inept kid, who never quite fit into Italy and never quite fit into the United States, would someday find a place, like Oz, where I could be accepted for exactly who I was. To realize that someone else could spend even more time in Oz, spend so much time writing about Oz, and even write a couple of definitely good books about Oz, know it well enough to complain that MGM was messing up its forthcoming movie by getting Dorothy’s hair color wrong, and yet still be able to write something like this, missing much of Baum’s entire point, is painful.

I just wish Thompson could have embraced Oz enough to lose her prejudices along the way. Then again, this is the same author who disdained to even mention the presence of the gentle, merry Shaggy Man, and also almost entirely ignored those retired workers Cap’n Bill, Uncle Henry and Aunt Em to chatter about princes and princesses instead. Perhaps I should be less surprised.

Mari Ness is, among other things, a Third Culture kid, although, before you ask, she’s forgotten all her Italian. She lives in central Florida.