Everybody, of course, knows Glinda, the mighty sorceress and the Good Witch of the South, thanks to a certain little movie and a moderately successful Broadway show. But what about her counterpart, the Good Witch of the North—the very first magical creature to meet Dorothy in Oz? Alas, nearly all the popular adaptations had forgotten about the cheerful little old lady—not surprisingly, since L. Frank Baum himself tended to forget his own character, leaving the door wide open for Glinda to snatch up the fame, the glory, and her very own line of jewelry.

But Ruth Plumly Thompson, at least, was intrigued enough by the character to give us a bit of the backstory of the Good Witch in The Giant Horse of Oz, as well as clearing up one of Oz’s minor mysteries—who, exactly, is ruling the four kingdoms of Oz?

If you’ve been following along, you know this certainly isn’t Ozma—who in any case, functions more as a Supreme Ruler over the other four rulers of the four kingdoms. When Dorothy had first arrived in Oz, the four countries—the lands of the Munchkins, the Quadlings, the Winkies and the Gillikins—had been ruled by two Wicked Witches and two Good Witches. Later books had established Glinda as the firm, all powerful ruler of the Quadlings and the Tin Woodman as the Emperor of the Winkies. (Both also presumably ruled over all of the other little kings and queens in the various tiny kingdoms that dot their lands. For a supposedly peaceful and prosperous country, Oz certainly seems to need a lot of rulers, but at least, in the Thompson books, it does not lack royalty of all kinds.) The Good Witch of the North remained nominally in charge of the Gillikin country, and as for the Munchkins—

Huh. What did happen to the ruler of the Munchkins? Just forgotten about?

Also forgotten about: the beautiful Sapphire City and Ozure Islands in the Munchkin country, kept trapped upon their lake by a dragon. For isolated, trapped people they are surprisingly up to date on the latest Oz news, aware not only of Ozma but also of the many mortal immigrants in Oz. A bored Ozure Islander repeats these tales to the dragon, who immediately recognizes that this might be his chance to have a mortal maiden (every dragon needs one)—and orders the Ozure Islanders to fetch a mortal maiden immediately.

It’s the entrance for one of Thompson’s more intriguing villains—not the sadly rather forgettable dragon, but the soothsayer Akbad. Intriguing, because unlike most Oz villains, he is evil not from greed, personal glory, doing bad things or collecting lions, but because he genuinely wants to save the Ozure Islands, and believes that kidnapping Trot is the only way to do so. Why Trot? Presumably because Thompson has already featured Dorothy and Betsy Bobbin in previous adventures, and believed that Trot was now due for another adventure—if one without her previous companion, Cap’n Bill.

Meanwhile, elsewhere in—Boston? Yes. Boston!—a stone statue of a Public Benefactor has come to life and started to stalk the city streets. Boston drivers, who apparently can only make way for little ducklings, react in classic Boston fashion by almost immediately attempting to run him over. (Apparently, Boston drivers were infamous all the way back to 1928. Who knew?) In a desperate attempt to evade the drivers, and in utter confusion at the city streets and lack of street signs, the stone statue leaps into an embankment, and falls through it all the way to Oz, which, um, apparently has been beneath Boston this entire time. It EXPLAINS SO MUCH. (Incidentally, this otherwise somewhat inexplicable outing in an American city provides what I believe is the first illustration of a car in an Oz book.)

Back in Oz, the Good Witch of the North, Tattypoo, and her dragon, Agnes, find themselves falling through a magic window and vanishing, much to the distress of young Philador, prince of the Ozure Isles, there for her help. A magical slate advises Philador to go to Ozma for help instead. (Good luck with that, kid.) Off he heads through the Gillikin Country, meeting a man with a literal medicine chest—opening his body allows him to pull out all kinds of medications, including things that sound suspiciously like things that should not be dispensed without a proper prescription, and other things that would quite possibly be illegal in Boston. They also meet Joe King, who, um, tells a lot of jokes, ruler of the Uplanders.

(Incidentally, when this assorted crew reaches Ozma, the Ruler of Oz is busy…playing Parcheesi. It’s enough to make me doubt the wisdom of anonymous magical slates. Fortunately, the Wizard of Oz is in the vicinity, or who knows what might have happened.)

As you might be gathering, summarizing this book, with its myriad appearances and disappearances and transformations, is surprisingly difficult. And yet the several plots all weave together into what is, for the most part, one of Thompson’s better works, a swiftly moving book filled with genuinely magical moments and some of her most lyrical writing. The Ozure Islands have a feel of what can only be called “fairy.”

But oh, the ending. The Good Witch of the North makes a surprise reappearance—she’d been gone so long I’d half forgotten she was even in the book—announcing that she is, in fact, the enchanted queen of the Ozure Isles, transformed into a busy, powerful, kindly, witchy—and elderly—woman by the spell of the evil witch Mombi. The destruction of the spell has transformed her back into a beautiful—and young—woman.

I am more than a little dismayed that Mombi chose old age as both punishment and enchantment. And even if the book had earlier softened this negative image by showing us just how happy, and useful, the Good Witch of the North could be, her transformation back to a young woman just reinforces the image of old age as punishment, and evil. And I rather wish the Good Witch could have regained her family without also (apparently) needing to lose her magic. It suggests, none too sublety, that women must choose either a career or a family—not both.

In contrast, that decidedly male stone statue from Boston, originally wanting to become a normal human, just like Peg Amy in Kabumpo in Oz), learns to accept himself for himself, and in the end, rejects any transformation that would alter his real self, exactly unlike the earlier, very feminine Peg Amy.

I do not think it coincidental that in Thompson books, more women are enchanted and transformed than men (although the men do not entirely escape, as we shall see), nor that with women, their disenchantments almost invariably end in marriage. Thompson’s male heroes return for starring roles in later books; her girls, with the exception of Dorothy, do not. It is not that Thompson was unable to create strong, self-reliant girl characters, as we will see, or that she was uncomfortable with creating a range of female heroines, since she did. But perhaps her experience with the very real boundaries faced by women caused her to set boundaries in her very unreal fairylands. It is also probably not a coincidence that her most self-reliant heroines, with the exception of Peg Amy, appear in her later books, after she had firmly established herself as a successful author, and was beginning to explore other writing outlets outside Oz.

Oh, and if the fail of playing Parcheesi when one of your friends has just been kidnapped and is desperately dashing through caves with the inept assistance of a merman isn’t enough for you, more Ozma fail, as the Ruler of Oz arbitrarily installs as new rulers of the Gillikin Country two people she’s apparently never even met—Joe King and his wife, Hyacinth. (The extreme difficulty of reaching their home, Up Town, does not bode well for the reign.) The supposed reasoning behind this decision: without a ruler, the Gillikin Country will be open to war and invasion, which, fair enough, I suppose, although a true sense of fairness would note that most of the wars and invasions in Oz seem to be focused on the Emerald City and not the Gillikin Country. Still, Ozma, whatever the invasion threat, would it have killed you to arrange for an interview, or at the very least invited the two to one of your fabulous parties, before installing two strangers to rule one fourth of your country? (Not to mention that no one bothers to consult any of the Gillikins about their preferences.)

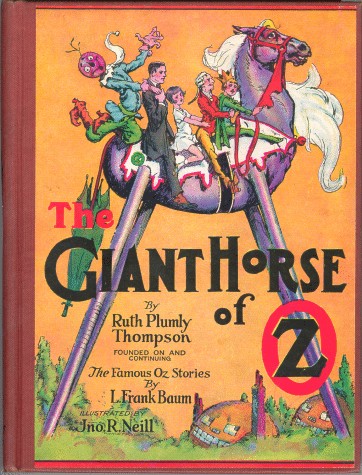

About the book’s title: you might have noticed that I haven’t talked all that much about the Giant Horse of Oz. Oh, he’s certainly in the book, and he’s certainly giant—he can stretch his legs to giant heights at will—but I have absolutely no idea why the book was named after him, since he’s a a minor character that appears only midway through the book, serving mostly as a giant sort of rapid transportation system, albeit one with jokes. I can only assume that Thompson’s publishers thought that “The Surprising Transformation of the Good Witch of the North, a Character You Probably Forgot About, Into Kinda a Hottie,” was just slightly too long for a title.

Mari Ness rather hopes that she, too, might someday rule a kingdom of Oz without even a job interview. In the meantime, she lives in central Florida, where she has so far been unable to wrest the rulership of the household from two cats.